When improving the operation of an ordinary greenhouse, people constantly face new and new problems. What is the essence of the main ones? First of all, plants grown in greenhouses require certain temperatures of air, soil, and water, which must change depending on the season and the needs of the plants. Even the same plant requires different temperatures at different times. Technically providing this is difficult, but possible. But finding out exactly what temperature the plant needs at the moment is much more difficult.

The second requirement is ensuring the humidity needed by plants. Here too there are problems. And the third requirement is supplying greenhouses with sufficient air enriched with oxygen and carbon dioxide.

To meet these basic physico-chemical needs of plants, many mechanisms have been created, sometimes very complex. Here, for example, is the AMT-600 equipment set. Semiconductor thermoresistances serve as temperature and humidity sensors here. The temperature regime is regulated using electromagnetic valves. To open the vents, hydraulic membrane jacks are used. But who gives the command to the actuators to open the vent or humidify the air? Instruments. For example, electropyrometers. And who gives the program to the instruments? A person. But no matter how experienced a person is, they never know exactly what the plant needs at the moment. Only the plant itself can know what it needs at the moment. But it is silent. Making it speak and act—that’s what needs to be achieved. This is an unending field of work for representatives of many fields of science.

Biologists will set themselves the task of deciphering the language of the cell. Representatives of the new science—bionics—will also find plenty of work. Of course, it’s useful to create a thermal locator modeled on a snake’s or use a frog’s eye as the basis for an optical design. But patents of living nature of this type still have limited application. If bionics methods can be used in agricultural production, this will be its most widespread application.

Radio electronics engineers will also not be left without work. After all, it is they who will need to design devices that will translate the most complex processes inside living cells into a system of electrical signals going to the actuators.

And many, many other scientists representing the most diverse specialties will find the most interesting work.

But why does all this relate specifically to the greenhouse? Because inside the greenhouse, a person is able to create the best conditions for the plant’s life, while in the open air—not yet. The more the external environment conditions meet the plant’s requirements, the faster it develops, the larger it becomes with less consumption of heat, electricity, and so on. The more protected ground devices there are in the country—and the trend toward their growth is obvious—the greater the savings will be expressed in numbers.

Learning to fully understand the plant is one of the most important and interesting tasks facing humanity. We can safely say that today or even tomorrow it is unlikely to be solved. This is the distant search of science. But protected ground devices pose many smaller problems. In solving them, young engineers and simply young mechanizers can already find application for their abilities today. This is the creation of various machines or even devices for working in greenhouses.

Even the simplest device requires a deep familiarity with the operation of a greenhouse. Making them, guys prepare themselves to create complex machines, learn that an ordinary state farm or collective farm greenhouse can become the most complex complex, where electronics, pneumatics, hydraulics, mechanics, and many other engineering sciences are combined. All this not only brings concrete benefits, but also forces the young designer to understand all the intricacies of greenhouses and hotbeds, to see the bottlenecks.

Everything said so far has related to the prospect—either distant or near, which requires scientific, technical, but not yet organizational solutions. However, there are many opportunities to set up greenhouses in places where this is not at all provided for. For example, in the body of concrete dams of hydroelectric power stations there are voids—so-called galleries. These are entire halls with huge areas. Equip them with lamps and mechanisms—fortunately, there’s no shortage of electricity—and already inside the huge concrete wall, around which waves roar, tomatoes and cucumbers quietly ripen. Power engineers should remember this.

And for house builders—about roofs. This is an ideal place for a greenhouse. Moreover, a modern urban residential building is a rather complex engineering structure with hot water supply, electricity, etc. Installing a greenhouse on the roof will not greatly affect the cost.

So, a greenhouse—seemingly such an ordinary device—hides great opportunities for creative reflection—from the deepest to the simplest. Here there is something to think about for scientists penetrating the secrets of the universe, and for engineers creating new designs or simply industrial structures, and for guys taking their first steps in technical creativity.

AND UNDER THE ROOF—RAIN

In greenhouses, certain temperature and humidity are usually maintained. So that they are not violated, special watering conditions are also needed. The water must be warm, its temperature below the ambient air temperature by no more than 2—4° C. So, even when supplying the greenhouse with tap water, it is by no means possible to put it into use immediately. Some intermediate containers are needed—tanks, brick reservoirs cemented inside and out. They are placed near the fireboxes or heating pipes are passed through them. When settling in such a reservoir, the water not only warms up, but also releases excess chlorine into the air.

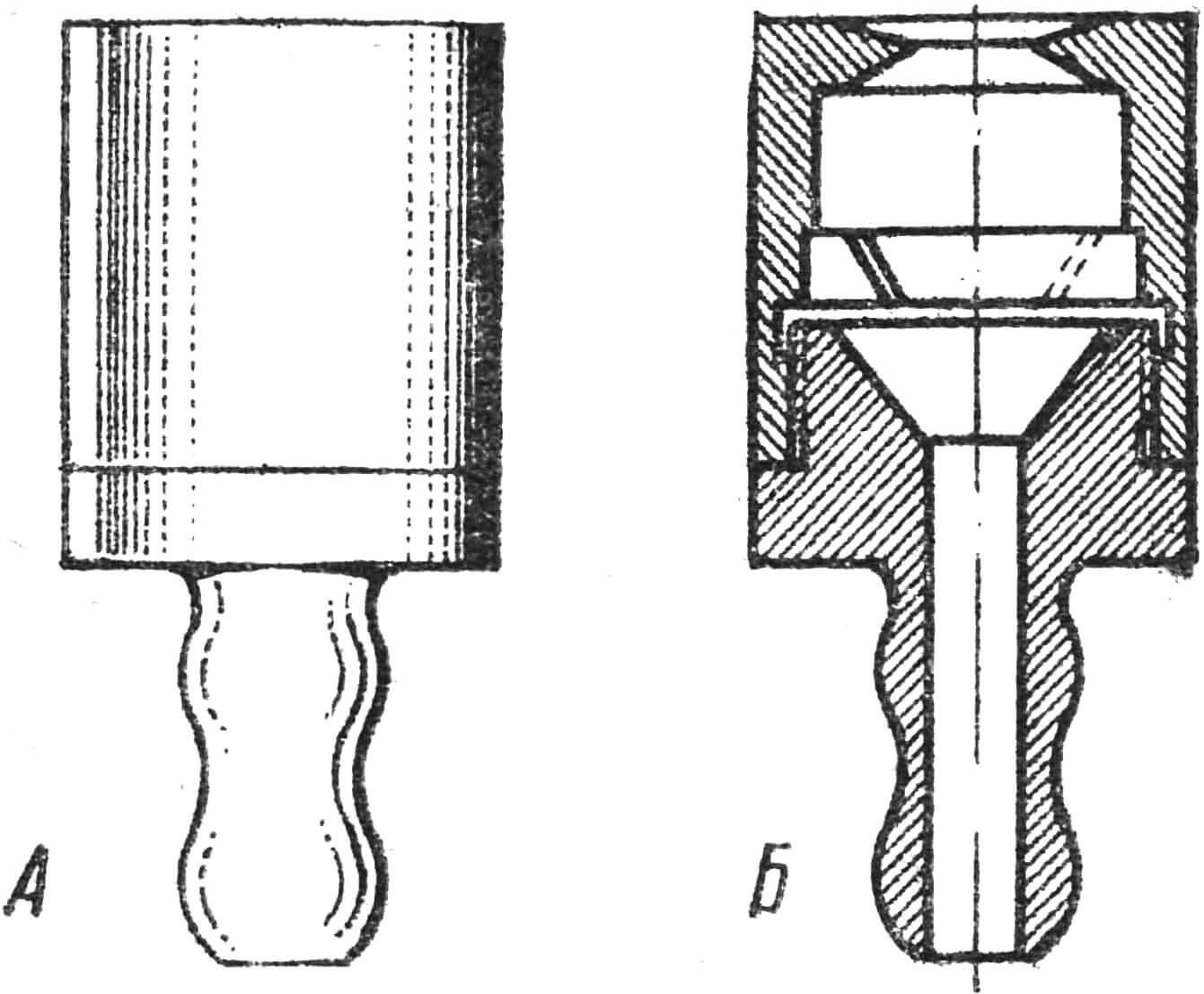

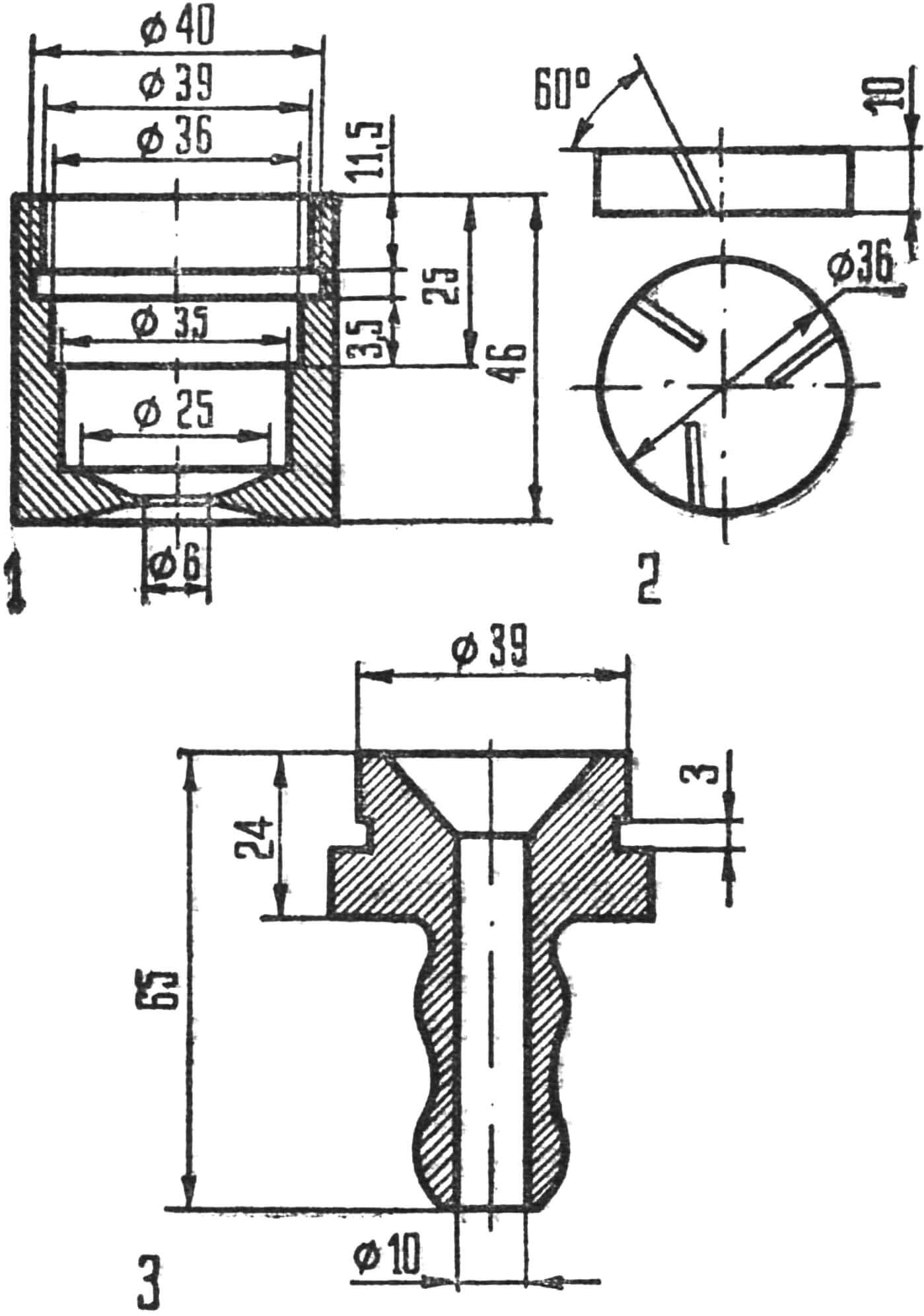

A — general view, B — cross-section; 1 — sprayer cover, 2 — impeller, 3 — sprayer body.

And the watering technique? From a hose? But with strong pressure it will erode the soil, bend and even overturn the stems and leaves of plants, and with weak pressure—it will take a long time. Therefore, in modern greenhouses, sprinkler irrigation is adopted. Usually, pipes with spray nozzles are installed under the ceiling, to which settled water is supplied. In industrial conditions, a whole system of instruments works here—humidity and temperature detectors, simply clock mechanisms that turn on the irrigation device at strictly defined intervals.

It is very important to make well-working spray nozzles. The plastic nozzles available for sale produce too large drops, and their operation requires very intensive water pressure. The nozzle, drawings and description of which are given here, sprays the stream more evenly. It allows combining sprinkling with foliar feeding with trace elements and mineral fertilizers. They are added to the water supplied through pipes to the plantings.

Spraying of the stream supplied under pressure is achieved thanks to oblique slots in the impeller. Moreover, unlike serially produced nozzles, this “sprinkler” is easy to disassemble and wash if it gets clogged.

CONSERVATORY ON THE WINDOW

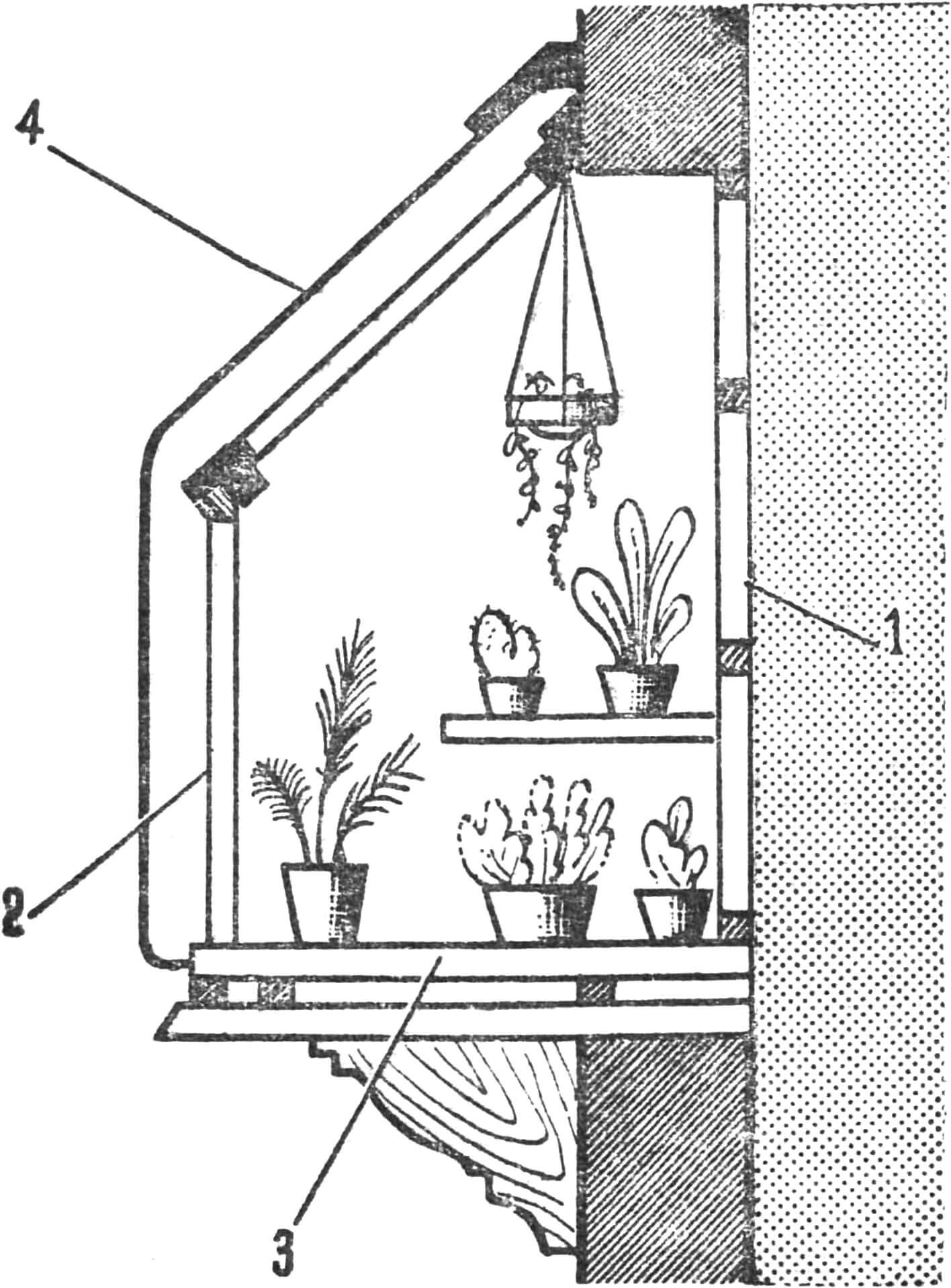

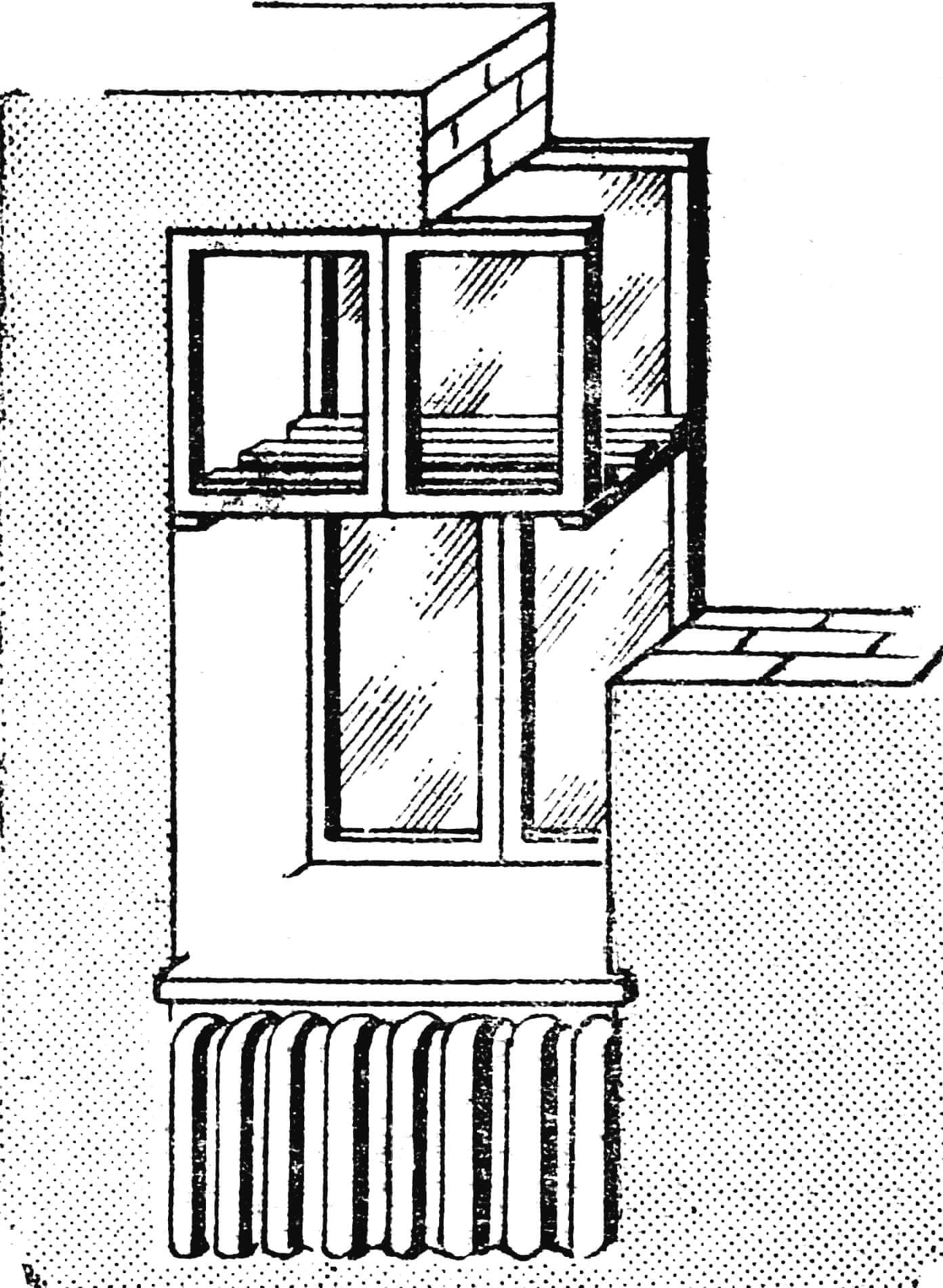

Making it is more complicated than an ordinary greenhouse on the windowsill. But the capacity of such a conservatory (see fig.) is about three times higher.

1 — inner, removable frame, 2 — outer frame (top is liftable), 3 — metal tray, 4 — bracket for shading device.

When making an extended window conservatory, you will have to remove the old frames together with the transoms and make new ones, carefully fitting each part. Inside the conservatory—across its entire width—from wall to wall, stretch shelves. Provide for lifting part of the outer frame for ventilating the conservatory and a louver device—for shading plants in hot weather and in spring, when solar, or as gardeners call them, monilial burns are most dangerous. In such a conservatory, you can install both a thermostat and an automaton that turns on plant spraying at strictly specified hours, and an automatic device for lowering the louvers in hot weather, and electric heating devices. But even without special heating, only by supplying warm air from central heating radiators, the temperature in this conservatory will be 3—5°, and under the sun’s rays—10—12° higher than in the room.

The bottom of the conservatory should be lined with a sheet of carefully painted or, even better, galvanized iron, bent in the shape of a bathtub. Otherwise, when watering plants with a sprayer, moisture will quickly disable all wooden units of the base of the “tropical kingdom.”

“COLD HOUSE”

Not every plant needs high temperature in winter, even one that does not tolerate frost. Here, for example, is a house rose that adorns the living corners of many schools. For roses to bloom profusely in summer, in winter they must be kept at a temperature of 12—14° and watered moderately. Roses rest at this time. Primroses rest, and geraniums, and even cacti.

And where will you find such coolness in hotly heated botany classrooms, in school conservatories? Some flower growers place plants between the frames. Also not very convenient—temperature fluctuations outside the window affect there too strongly, and in new buildings the frames are made double, with a distance between the panes of 50— 60 mm, where you can’t even put a tiny cactus.

Breeder-experimenter V. G. Chuchkin came up with a simple greenhouse for such plants (see fig.), placing it not on the windowsill, but in the upper part of the opening—away from the radiators and still in the light. Three walls and the ceiling of such a greenhouse are the window walls and the top glass. Two slats are nailed to the side walls and the base of the greenhouse—its floor—is attached to them. It remains to make and glaze tightly fitted doors. The greenhouse is ready. So that it still does not darken the room too much, its floor is better made of thick—5—6 mm—glass, and plant pots should be placed in separate trays.

The figure shows V. G. Chuchkin’s greenhouse. Its dimensions are dictated by the window on which you decide to place it.

G. KISELEV

FILM COVERINGS

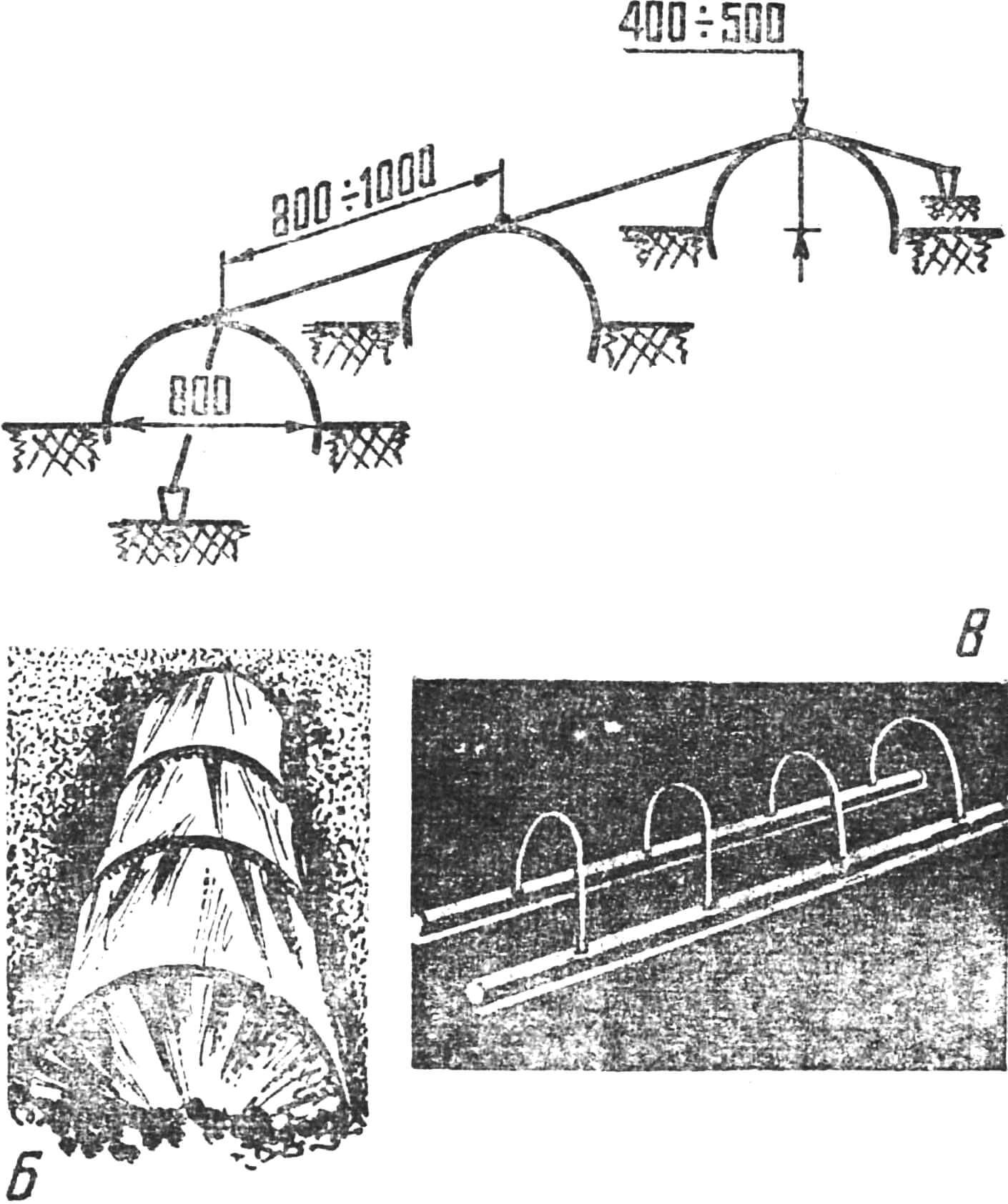

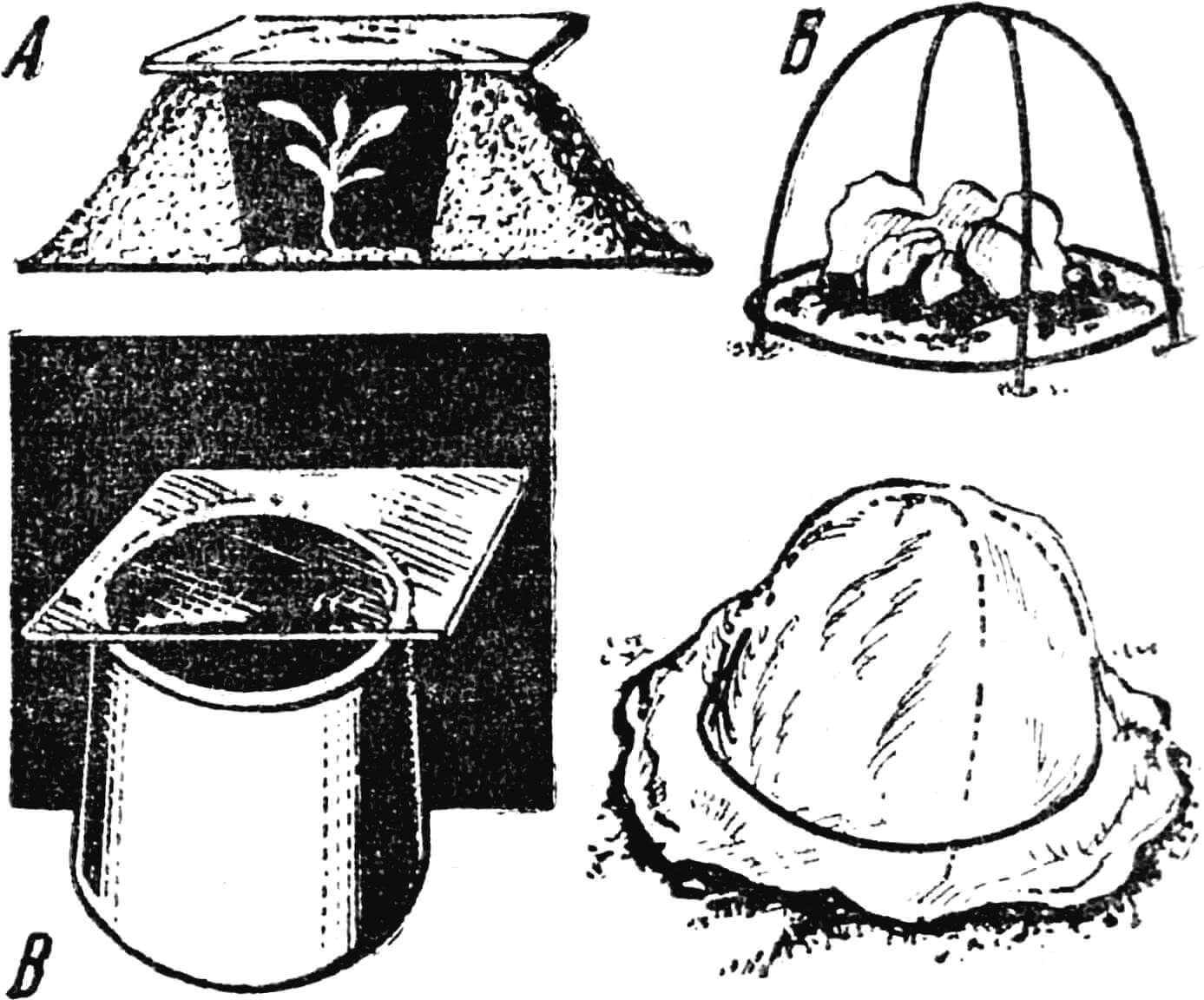

Sometimes a greenhouse can be replaced by compact film coverings.

On cloudy days, the air temperature under the film is 4—5°, on sunny days—10—11° higher than outside, and during frosts it is always 2—3° above zero.

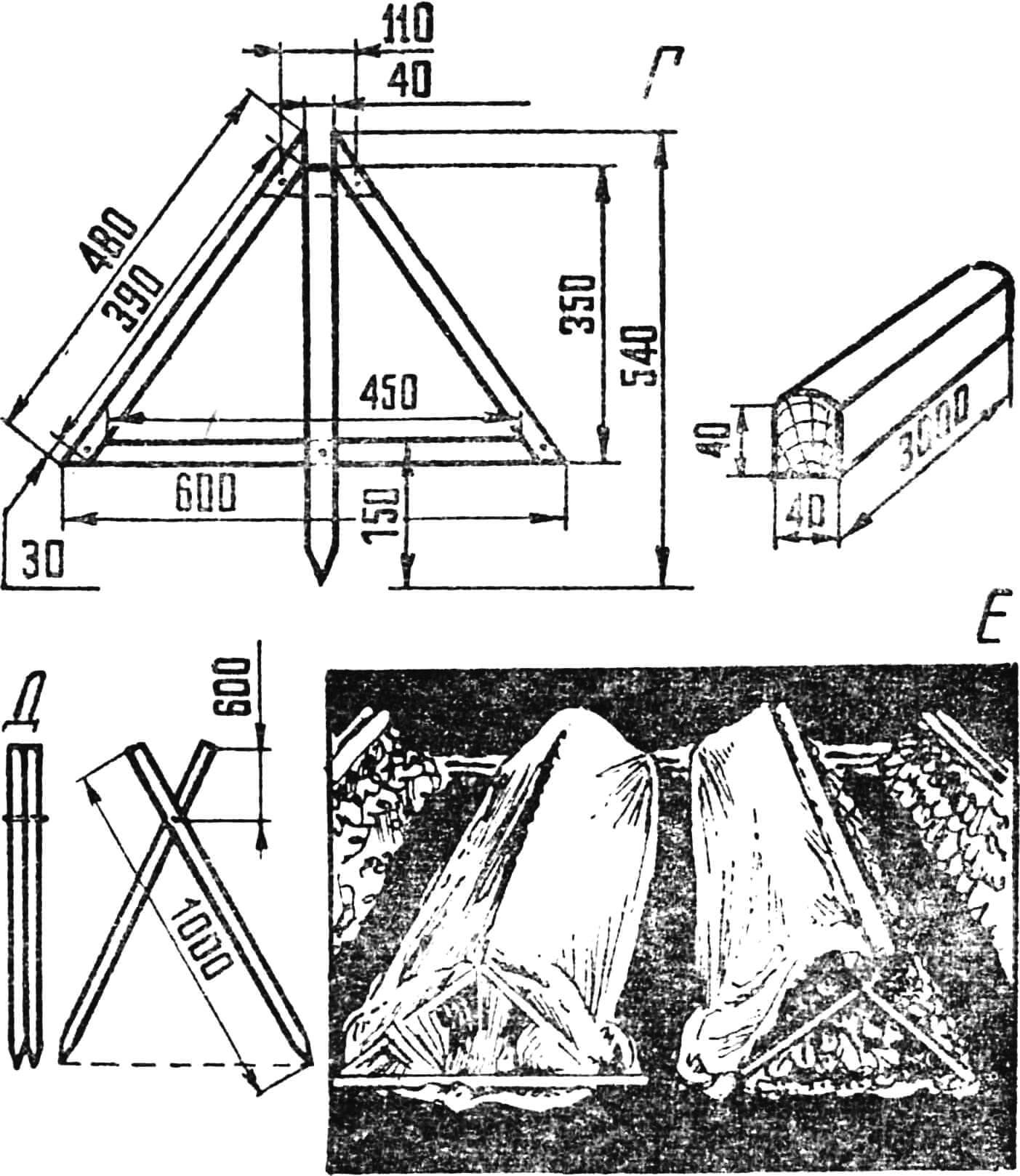

Most often, for growing seedlings on unheated ground, frames covered with film are used (fig. 1). The frame hoops are made of wire 6—8 mm thick or from rods (fig. 1,a) and placed at a distance of 800—1000 mm from each other. Their ends are buried in the ground up to 15 cm. So that the film covering the frame does not sag, a thin wire (or twine) is stretched along the top of the hoops, the ends of which are connected to stakes driven into the ground to a depth of 25—30 cm (fig. 1, b). Wire frames can be made portable without burying them. In this case, the hoops are attached to two wooden beams (fig. 1, c).

They can be made in the form of triangles (fig. 1, d) from bars with a cross-section of 40×40 mm, spaced at a distance of 3—5 m. Wire hoops are placed between them (so that the film does not sag).

Wire is also stretched along the top of the triangles.

For collapsible trestles (fig. 1, e), bars with a cross-section of 30X30 mm and a length of 1000 mm are taken. When buried in the ground by 25—30 cm, the width at the bottom will be 75—80 cm, and the height 45—50 cm. Slats are laid on the opened trestles.

The film should be longer than the frame structure by 120—130 mm to cover the ends and wider by 20—30 cm for side fastening. To do this, the edge of the film is laid on the flat side of a semicircular slat, then strips of old oilcloth (braid or any fabric), and all this is nailed with small nails. A second slat is also placed with the flat side and both slats are fastened with longer nails. The edges of the film can also be welded with an iron. And for ventilation, it is rolled up from the leeward side and wrapped inward (fig. 1, f). If there are no slats on the frame devices, the edges of the film are covered with earth.

Frames are installed in a place protected from cold winds on well-warmed soil, with end sides from east to west.

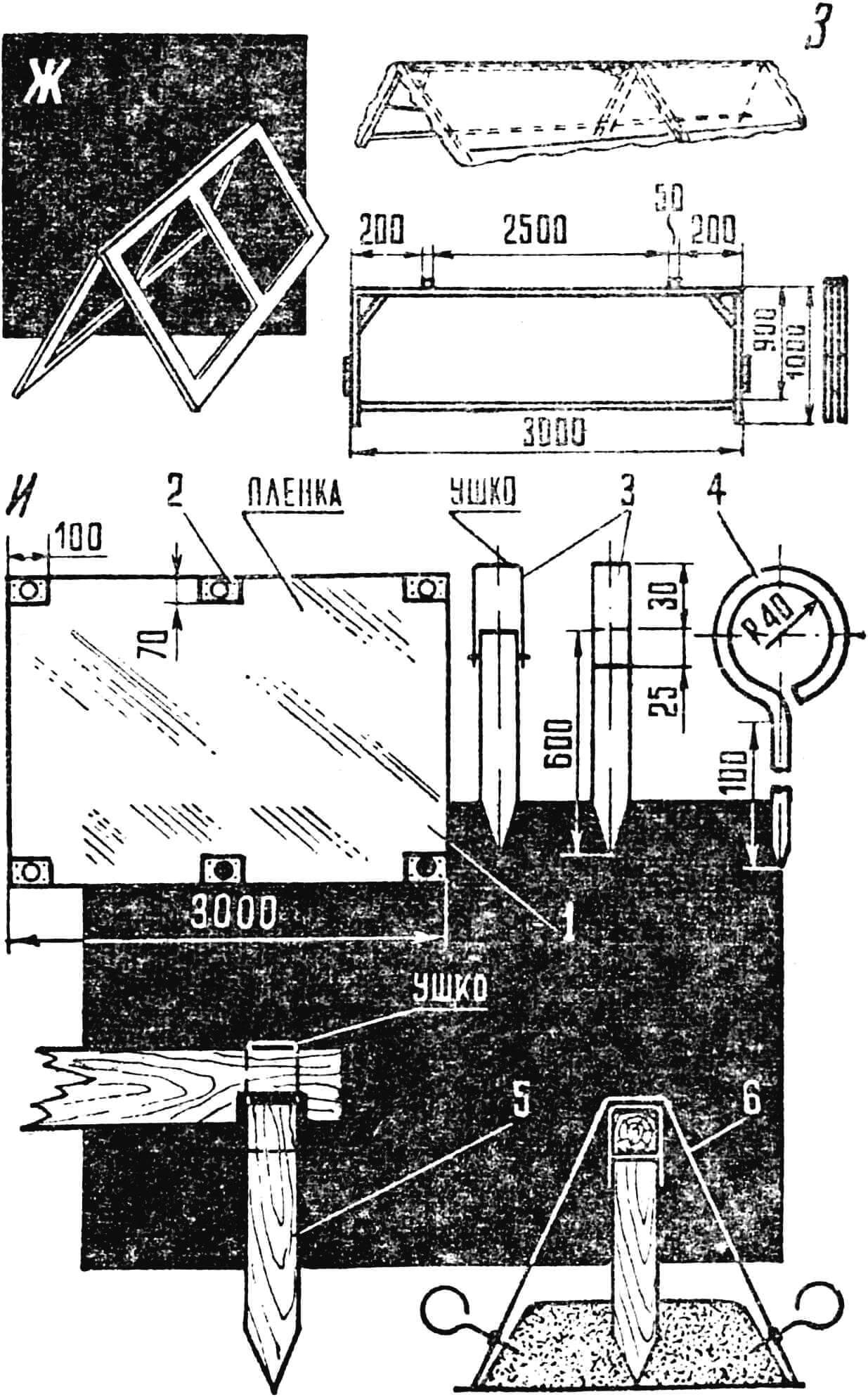

The Latvian Agricultural Research Institute proposed a portable double-leaf frame with film stretched on it (fig. 1, g). This design is distinguished by high wind resistance. Almost the same type of coverings are made by vegetable growers of the “Ivanovsky” state farm in Ivanovo Region (fig. 1, h).

Figure 1, i shows a method of covering with film proposed by amateur vegetable grower A. Ponomarev. Along the edges of a film of standard width and 3 m long, he nails plywood boards so that the film is tightly clamped between them. In the center of the boards (the distance between them is approximately 1 m), he makes holes with a diameter of 6—8 mm. A set of stakes with a cross-section of 25×25 mm and a length of 60 cm is also needed. One end of the stake is pointed, and an eye made of a metal strip 20 mm wide is fixed on the other. The stakes are connected with a wooden slat with a cross-section of 25X30 mm and a length of 30 thousand mm and placed on the beds. The resulting frame is covered with film with pins fixed on the plywood boards. Stakes and slats are installed once per season until warm weather arrives. The covering is ventilated through open ends. In cold weather, they can be closed with triangles.

Individual coverings (fig. 2) are used to protect vegetables planted far apart from each other (tomatoes, melons, watermelons, pattypan squash, zucchini, and others) from frost. Where the soil warms up quickly, planting is done in deepened holes (fig. 2, a), which are covered from above with glass, film, or newspaper during frosts.

Agronomist V. Butkevich recommends film caps for individual plant covering (fig. 2, b). The base is a wire arch stuck crosswise into the ground. A hoop presses the film to the ground surface. Cylinders covered with a piece of glass (fig. 2, c) are cut from roofing felt or tar paper.

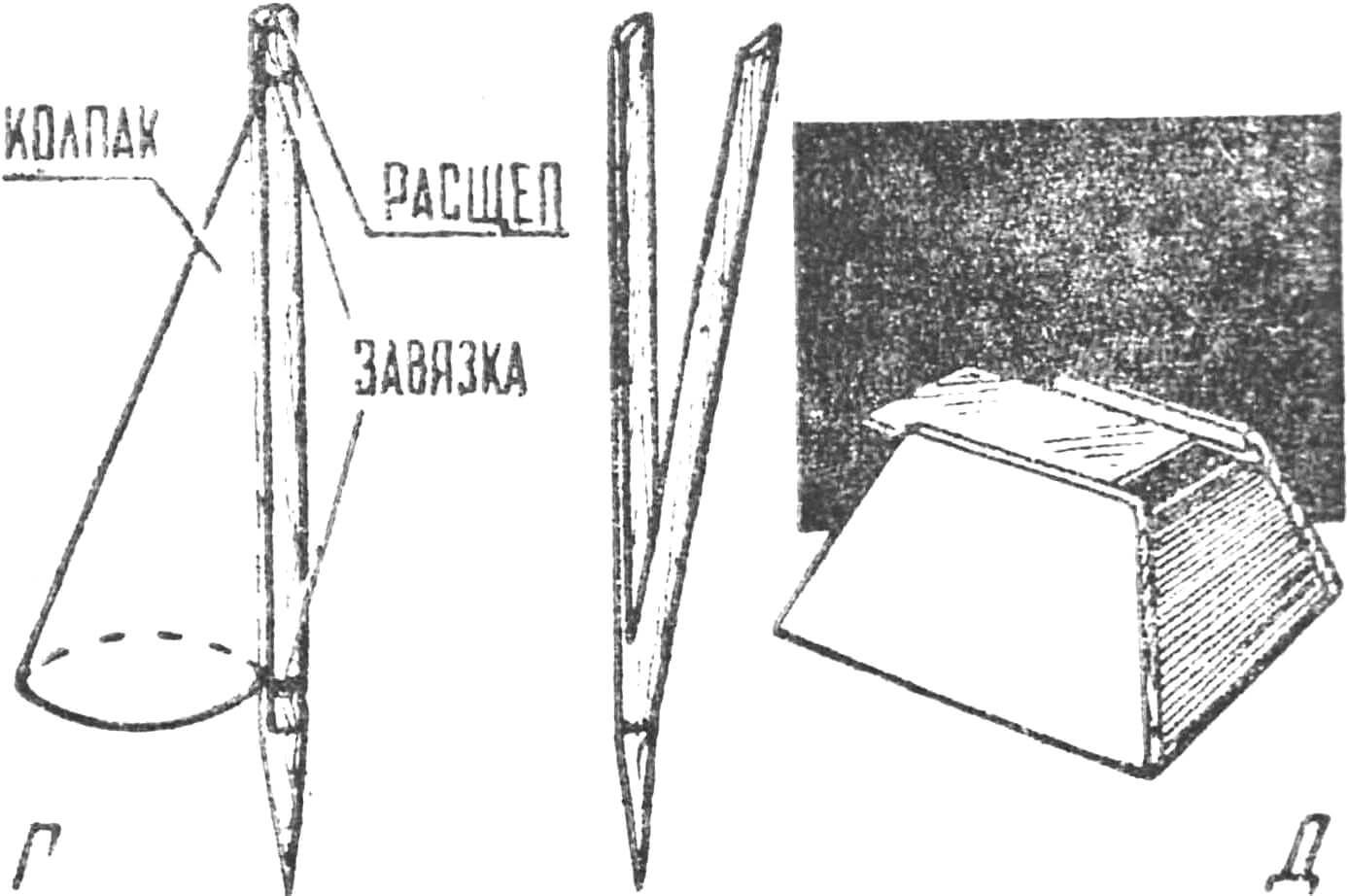

Amateur vegetable grower F. Rudakov from Tambov Region covers plants with caps made of transparent film. A piece of it, rolled into a cone, is secured with a twig (fig. 2, d). If there is no film, then cones in three to four layers can be made from newspaper. Special transparent boxes are less commonly used for individual covering (fig. 2, e).

YU. REISLER, Candidate of Technical Sciences

“Plus or Minus One Degree”

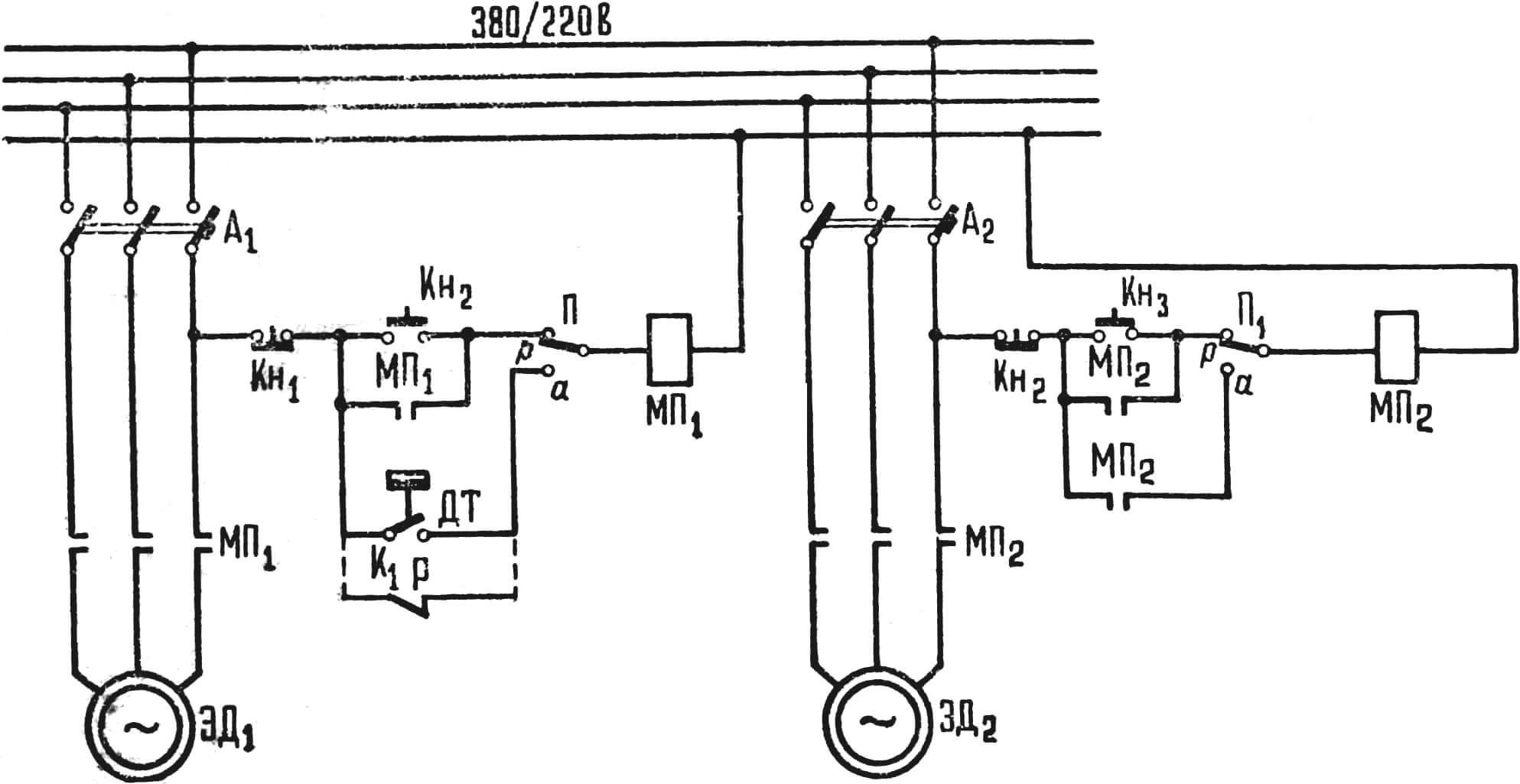

These are the strict limits within which air temperature fluctuations in a greenhouse are allowed. But with manual control of heating systems, it is impossible to fight the influence of the “street” on the greenhouse climate. Frosts and thaws inevitably cause large temperature fluctuations in the greenhouse, and unfavorable conditions are created for plants. What to do?

A1, A2, MP1, MP2 — selected according to power and type of motors.

In greenhouses where heating units with electric or water heaters are used for heating, it is relatively simple to install automatic temperature regulators (fig. 1) with temperature sensors (DT) of the DTKB-50 type. When the temperature changes, the free end of the sensitive element—a bimetallic spiral—moves and closes or opens a contact in the magnetic starter MP1 power circuit. When installing the sensor, pay special attention to ensure that moisture does not get on it.

When preparing the circuit for operation, it is necessary to close the automatic switches A1 and A2 and switch switches P and P1 from position “r” (manual control) to position “a” (automatic control). The sensor is preliminarily set to the specified temperature. If the air temperature in the greenhouse is below normal, the sensor contacts DT close, magnetic starter MP1 operates and motor ED1 of one of the units turns on. At the same time, the block contacts of magnetic starter MP1 connect the winding of magnetic starter MP2 of motor ED2 of the second unit to the network. In exactly the same way, any number of heating elements can be turned on sequentially. When the temperature reaches the set value, the sensor turns off the units. Then turns them on again, etc. The frequency with which the adjustment cycle repeats depends mainly on the difference between the greenhouse air temperature and the “street” temperature. Therefore, with a large temperature difference, it is better to keep some of the heating units constantly on, switching them to manual control.

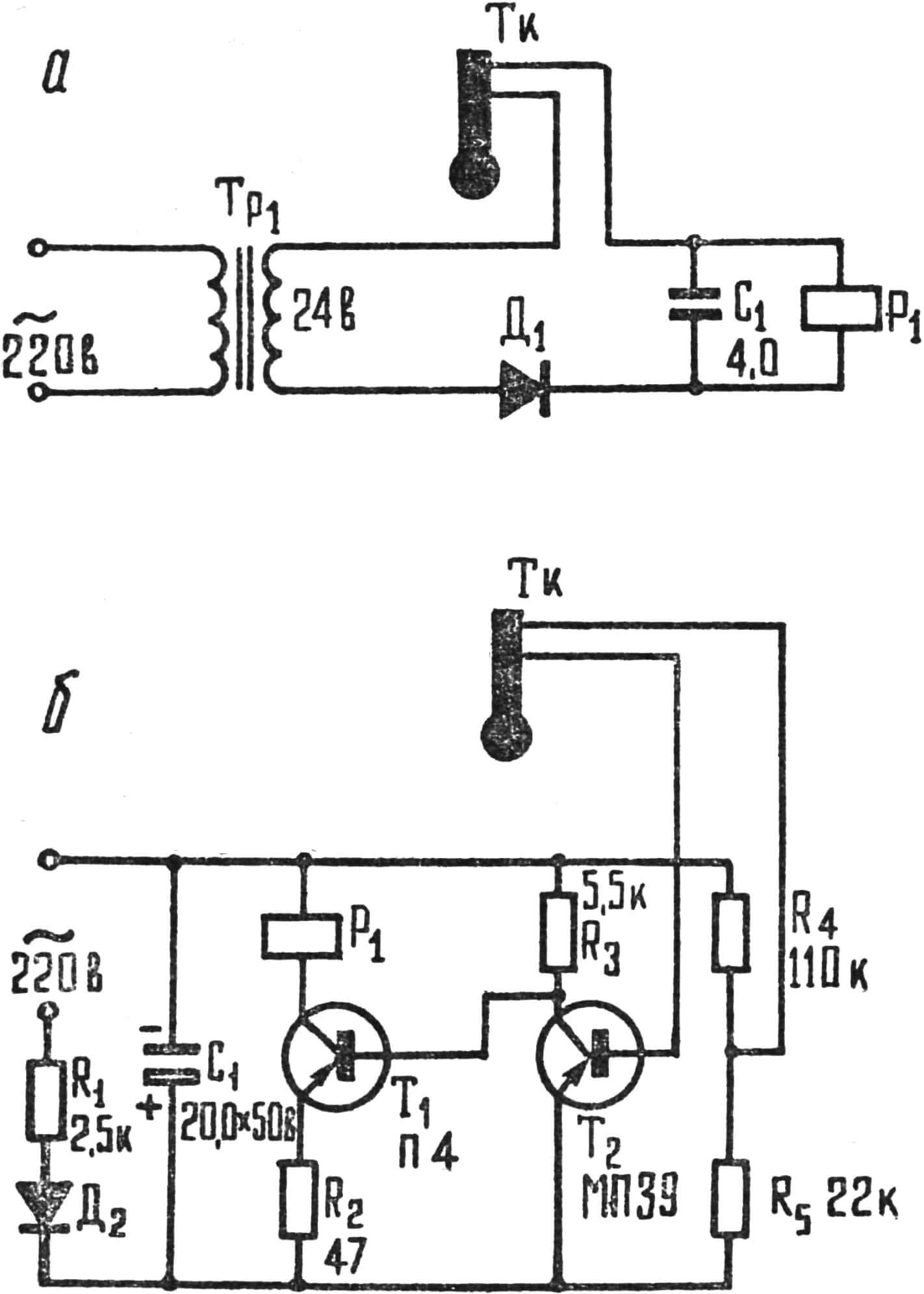

a — with step-down transformer (C1 — type MBGL, P1 — MKU-48S); b — with electronic amplifier (C1 — KE-1; R1, R2 – VS-0.5; R3 — R5 — VS-0.25; T1 — P213—214; T2 — MP39; at input voltage 127 V R1=1 k; P1 — MKU-48).

Instead of the DTKB sensor, mercury contact thermometers of type TK or TPK, produced by the Klin Thermometer Plant, can be used in the equipment. In this case, the circuit becomes more complicated, since the thermometer contacts allow very low current load—0.2 A, 2 W. Figure 2 shows two variants of the contact thermometer connection circuit—with a step-down transformer and with a semiconductor amplifier. The normally open contacts of output relay P1 are connected to the magnetic starter MP1 power circuit.

G. GULYAEV, Candidate of Technical Sciences

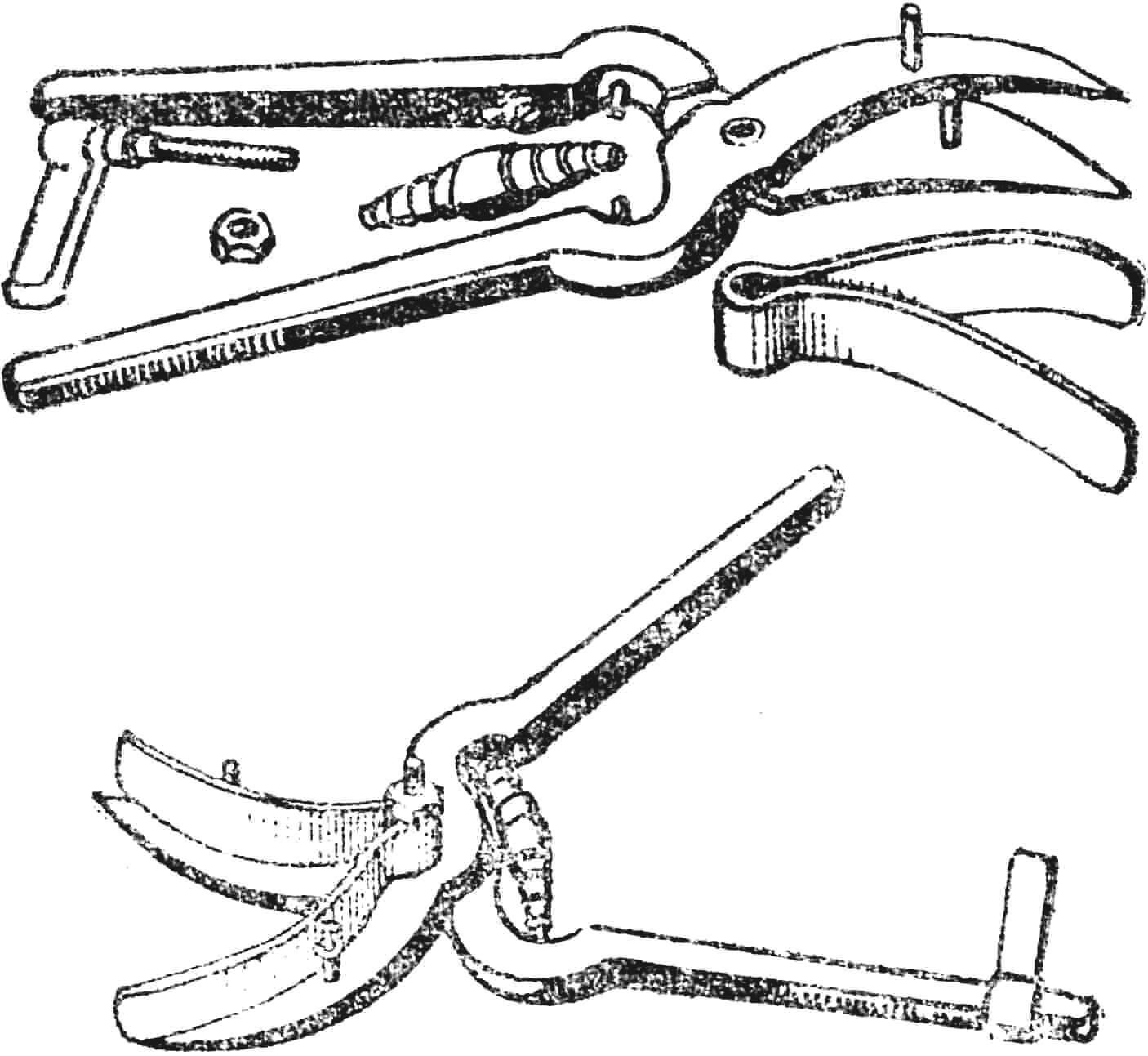

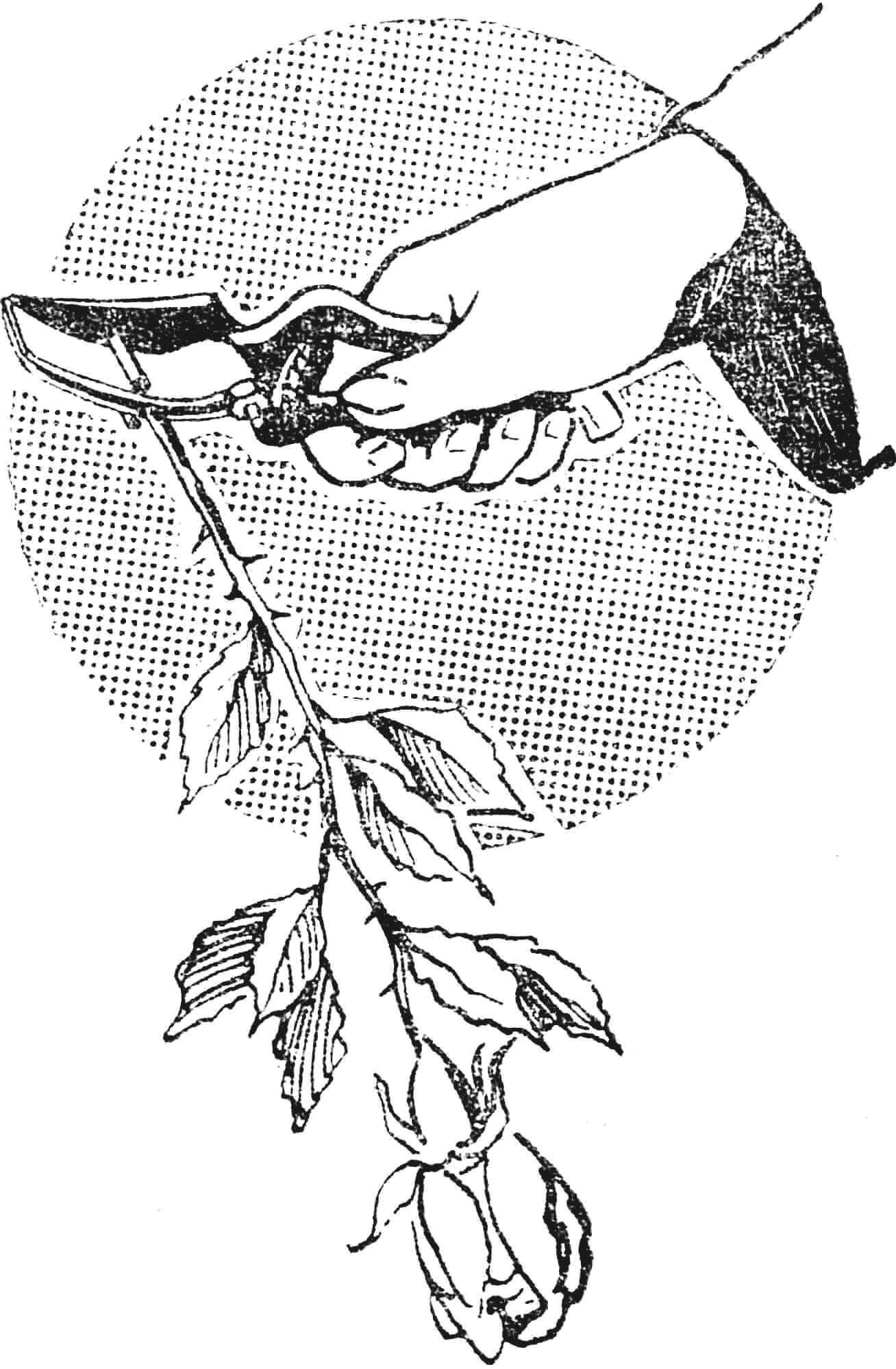

IMPROVED SECATEURS

Imagine a flower picker in a conservatory. In one hand secateurs, in the other a basket. Here a rose is cut, and it lies on the ground. Or you have to put the basket on the ground to catch the flower.

A small improvement to the secateurs (see fig.) will help ease the work of flower pickers. It consists of the following. The screw that regulates the length of the secateurs blade is replaced with a screw of the same diameter, but 20 mm longer. Two rods Ø 4 mm, 20 mm long, are welded to the blades. A steel plate is also needed, which is bent as shown in the figure. It should serve as a stem grip.