Among elastic oscillations of air, ultrasound (from Latin ultra — beyond, more, above), inaudible to the human ear and with a lower frequency limit conventionally taken as 20 kHz, has long attracted special interest. Insects, bats, and even cetaceans make successful use of this natural gift: some for communication, others for hunting, others for locating terrain and avoiding obstacles in poor visibility.

By studying the role of ultrasound in the animal world, humans have adopted some of nature’s revealed “patents” for their own use. In particular, the “silent” whistle: the hunter blows it, and to this call—inaudible to many—a dog emerges from the thicket, correctly responding to the commands given by such a whistle.

Ultrasonic echo sounders are no less popular; the “locators” of cetaceans and bats can rightly be considered their analogues. By sending with this device and then receiving ultrasound pulses reflected from the bottom, the ship’s captain obtains up-to-date information on water depths.

Ultrasound finds other applications too. In chemistry, for instance, producing fine emulsions; in medicine, examining internal organs; in metal defectoscopy, detecting hidden cavities and cracks in cast parts. Fans of popular-science TV may recall the striking experiment shown on central television where a peacefully standing cup suddenly shatters, and the explanation: such destruction occurs when the frequency of ultrasonic irradiation coincides with the resonant frequency of the brittle vessel, and that micro-explosions triggered by ultrasound are promising for cleaning various surfaces.

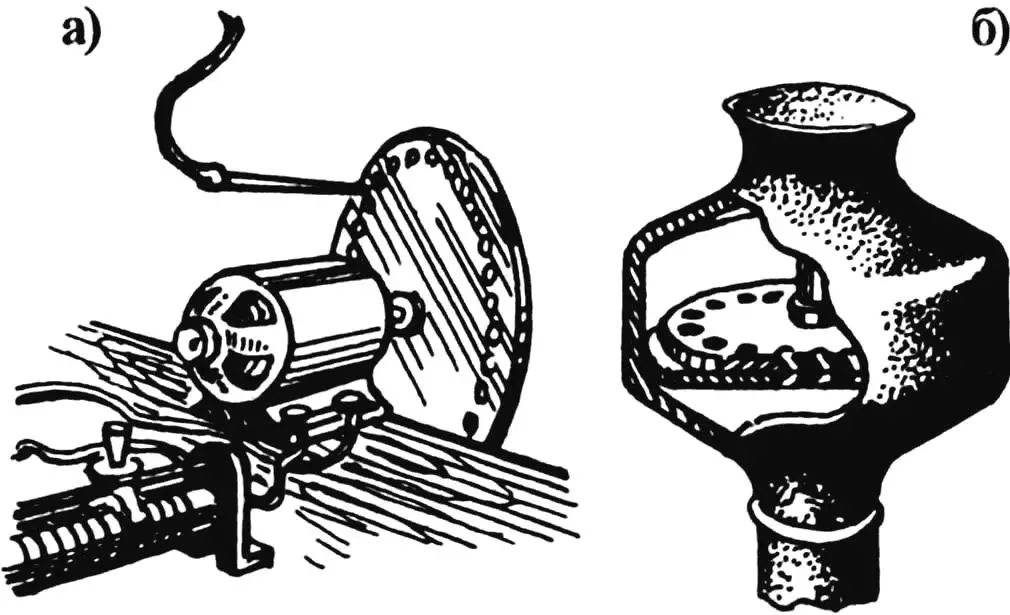

An unconventional way of generating ultrasound is by periodically interrupting a narrow, directed air stream with a rotating disk that has many holes around its circumference. When the stream is cut off by the advancing wall, a rarefaction forms behind it, immediately filled by the surrounding air.

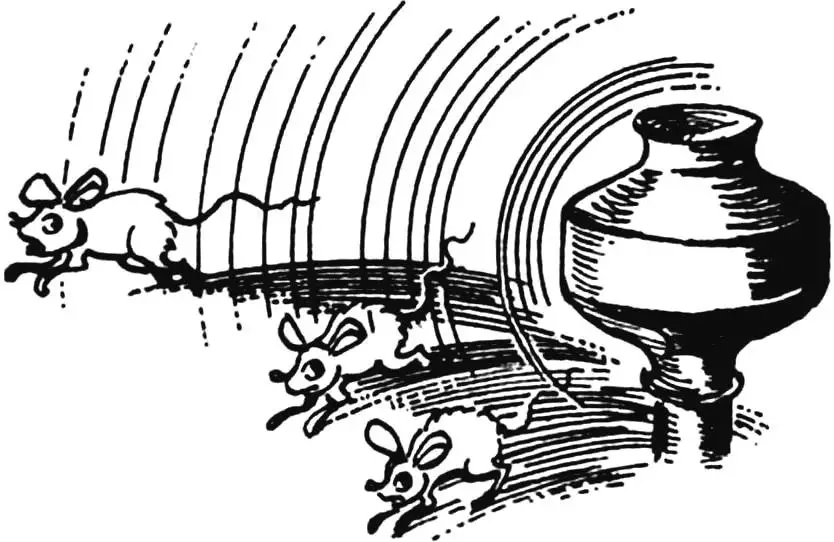

The spectrum of the resulting air oscillations contains many frequencies that are multiples of the fundamental (unit: Hz), which is given by the product of the number of holes in the disk and its rotational speed (rev/s). Ultrasound is of course present here too and can be used for various purposes, including repelling harmful rodents (there is evidence that mice and rats, once accustomed to monotonic ultrasonic oscillations, cannot tolerate periodic frequency changes in the 25–50 kHz range).

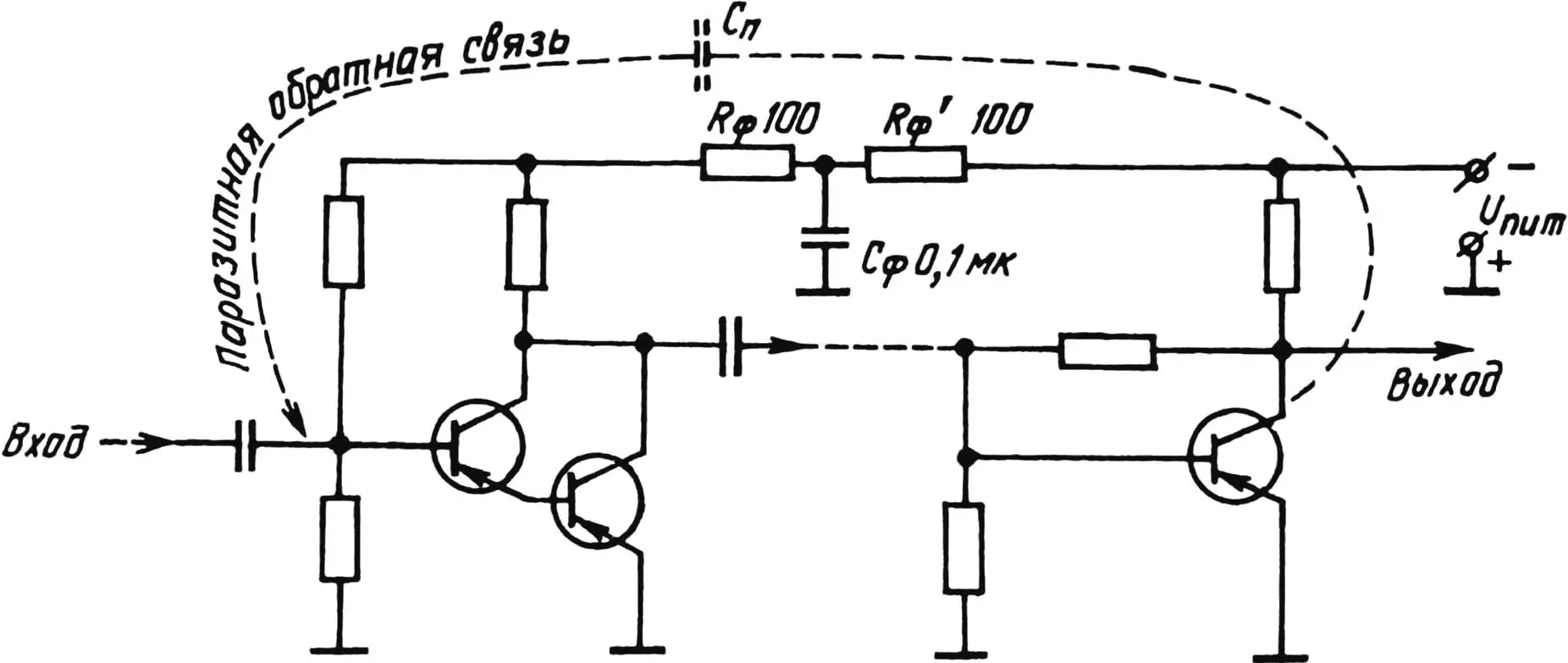

Here is an example of the adverse effect of ultrasound. It is encountered when operating devices with radio-electronic stages that have high gain, when so-called parasitic feedback between input and output makes itself felt. The result is not only ultrasound partly reproduced by the transducer, which can make people’s ears ache, but also hidden overload of the radio-electronic stages—imperceptible to humans—that can lead to their failure. This unwanted effect of parasitic capacitance is counteracted by introducing special (e.g. resistor-capacitor) filters RфCфRф into the common supply circuit of the stages.

Radio-electronic methods also prove useful in solving other, not only technical, problems. For example, in combating the aforementioned rodents by exploiting their specific reaction to ultrasound. Readers of the magazine who like to build everything by hand can be recommended one such anti-mouse (anti-rat) design: an auto-switching ultrasonic emitter.

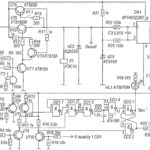

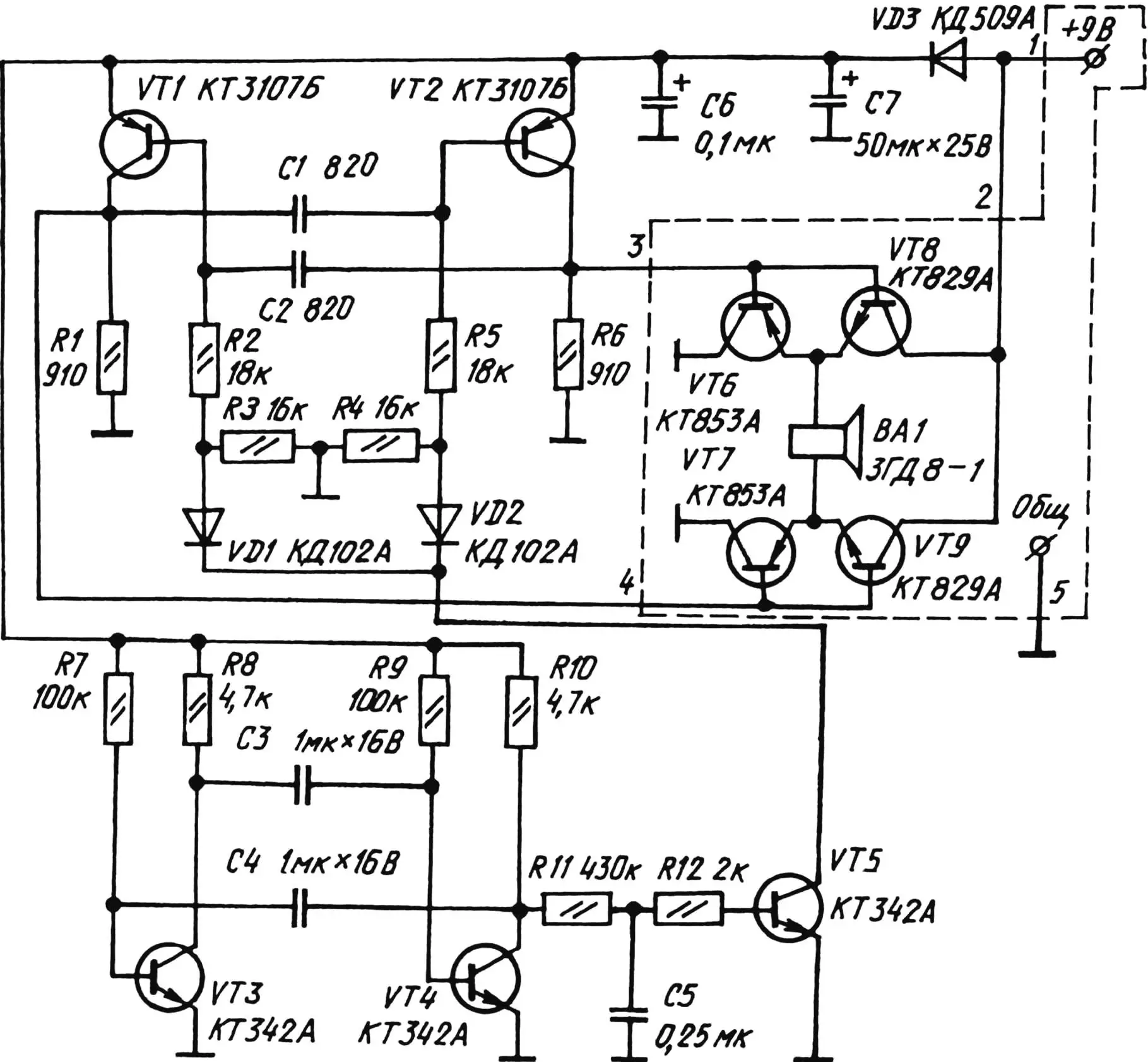

The homemade “Antigryzun” (anti-rodent) device contains two electrical oscillators, a powerful output stage, and an electrodynamic ultrasonic emitter that “drives” the surrounding air. The main oscillator, operating in the ultrasonic range, is built as a symmetrical multivibrator on transistors VT1–VT2. The corresponding switching frequency is set by the capacitance values of capacitors C1 and C2 and the resistance of resistor pairs R2–R3 and R4–R5. With the values given on the schematic, it is approximately 25 kHz. If resistors R3 and R4 are shorted, however, the frequency doubles. This is what the second oscillator, built on transistors VT3–VT4, does about seven times per second.

Rising and falling voltage at the collector of VT4 controls transistor VT5, turning it on and off. The open collector-emitter path of this semiconductor triode shunts (via diodes VD1 and VD2) resistors R3 and R4, so the main oscillator’s frequency increases. The switching of VT5 is not abrupt but gradual. Thanks to the integrating network R11C5, the result is a kind of “sweep” over the range from 25 to 50 kHz.

The same frequencies are used by the output-stage transistors VT6–VT9 operating in switch mode, driven by alternating pulses at the collectors of VT1 and VT2. A high level at the load of VT1 turns on VT9, and a low level at the output of VT2 turns on VT6. As a result, current from the supply flows in one half-cycle of the oscillator through BA1 from bottom to top, and in the other—when VT7 and VT8 are on—in the opposite direction, making the loudspeaker work in the ultrasonic range where it is not normally used.

Common parts are enough to build such an emitter. In particular, MLT-0.25 resistors and capacitors KLS (C1, C2), K73-11 (C5, C6), K50-20 (C7). A “high-frequency” dynamic driver such as ZGDV-1 is suitable as the transducer.

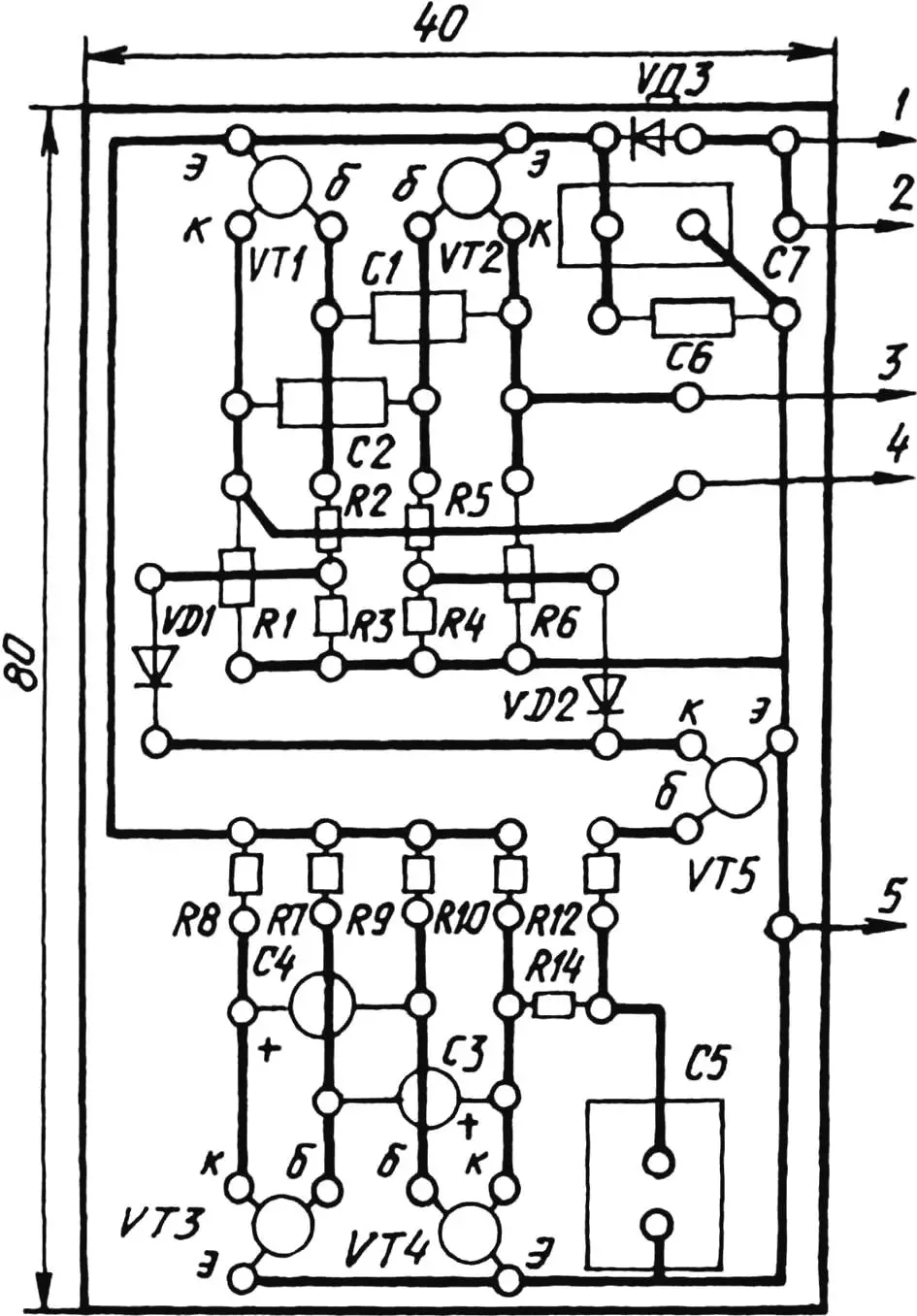

All parts of the device except the power transistors VT6–VT9 are mounted on a pseudo‑printed (cut-out) board made of single-sided copper-clad glass-epoxy 1.5–2 mm thick. Transistors VT6–VT9 are used with rectangular heatsinks, which are either attached to the board or mounted directly on the enclosure, with no electrical connection between heatsinks.

Trial runs of the ultrasonic emitter can be done powered by six series-connected cells. In normal operation the device runs continuously, so for supply use a rectifier with a filter rated for 2.5–3 A at 9 V.

«Modelist-Konstruktor» No. 4’2001, P. YURIEV