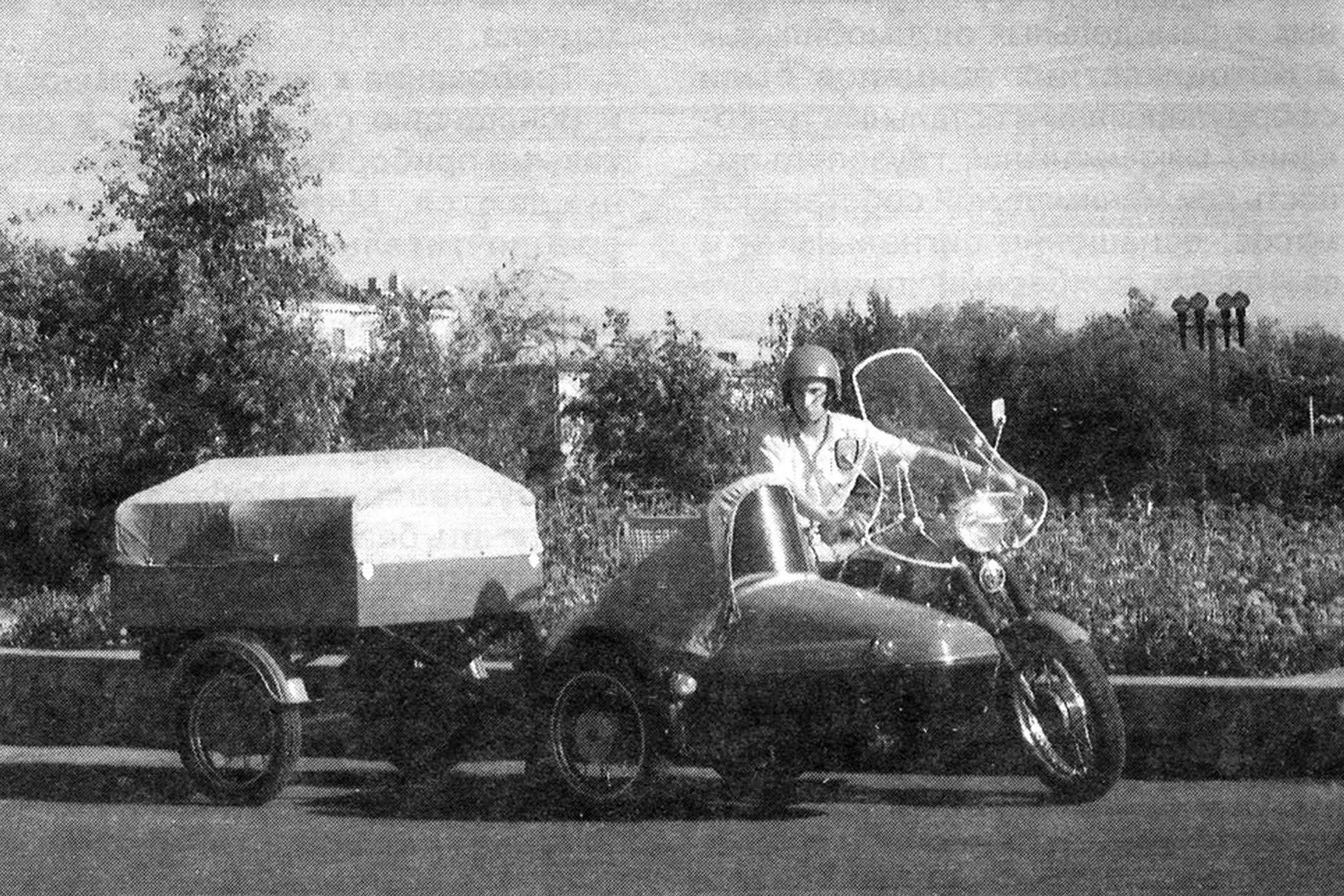

Is such a thing possible? It would seem hard to imagine this elegant, fast motorcycle in the role of a truck. Nevertheless, it handles the role of a heavy hauler admirably, thanks to a reliable and durable engine with good finning and sufficient torque across the entire crankshaft speed range.

It should be said that before this my Jawa-350/634 with a Velorex-562 sidecar had been in use for ten years. The mileage was about 60,000 km. With a full load the motorcycle confidently covered considerable distances both on highways and on dirt roads. Off-road and heavily rugged terrain were no obstacle either. The motorcycle’s trouble-free service under these conditions is sufficient proof that in normal conditions, besides three riders, it can also carry a substantial load. But where to put it? The sidecar’s load capacity is limited to 105 kg, and fitting an extra luggage rack on it made no sense. The logical conclusion was to build a cargo trailer.

The impetus for action was the author’s coming across the frame of an abandoned cargo scooter “Muravey” on a vacant lot. Its well-preserved body simplified the design task. Overall, the trailer layout was determined by the parts and assemblies that could be obtained: wheels from a Voskhod motorcycle, shock absorbers, stop lights and turn indicators from a Jawa.

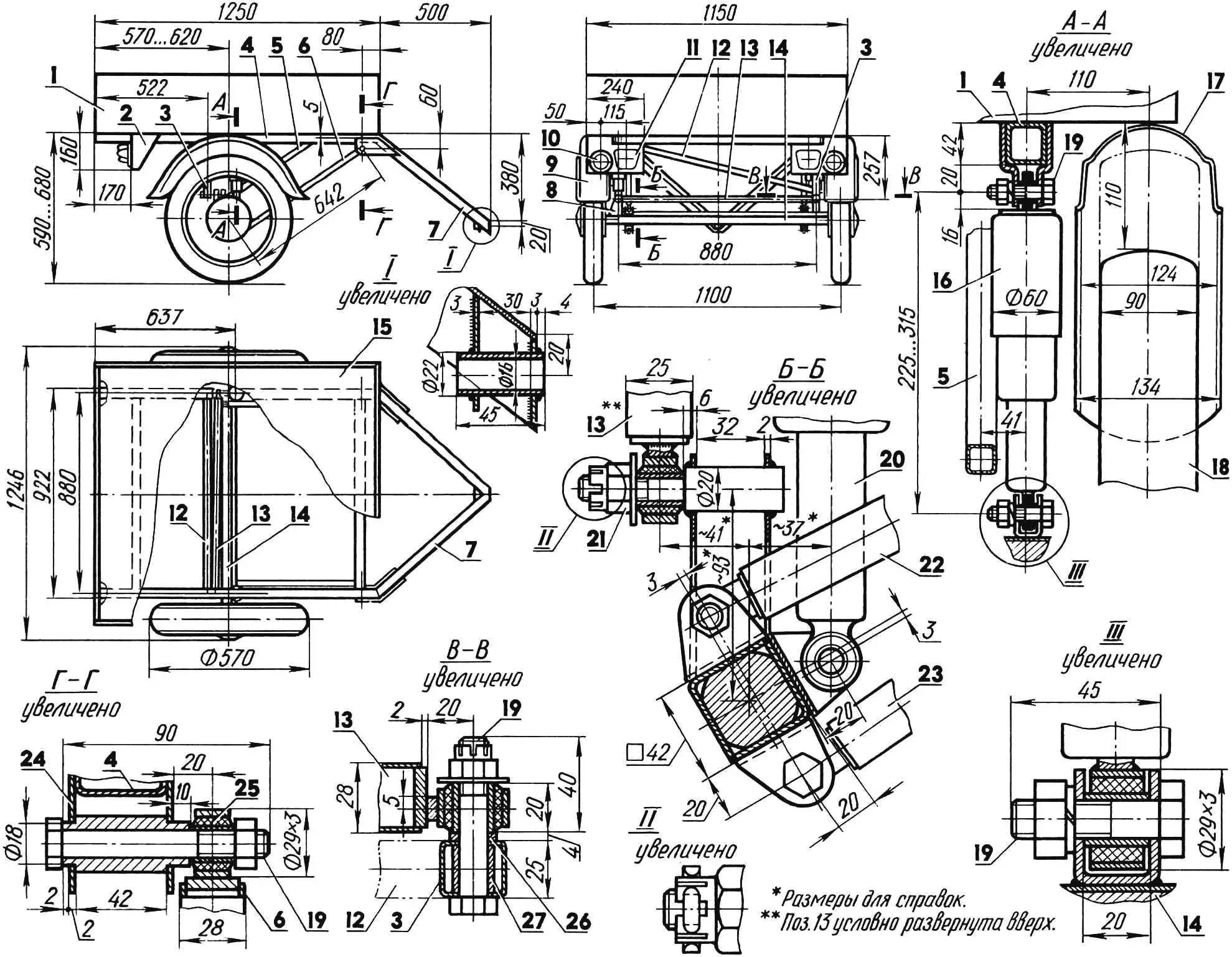

1 — body (from Muravey scooter); 2 — lighting bracket (steel, sheet s2); 3 — stanchion (tube 28×25); 4 — frame (angle 42×42); 5,22 — upper longitudinal bars (tube 28×25); 6,23 — lower longitudinal bars (tube 28×25); 7 — drawbar (angle 42×42, L766); 8 — transverse reactive bar bracket (steel, sheet s2); 9,17 — mudguards (from Voskhod motorcycle); 10 — turn indicator (from Jawa motorcycle); 11 — stop light (from Jawa motorcycle); 12 — strut (tube 28×25); 13 — transverse reactive bar (tube 28×25); 14 — axle assembly; 15 — body floor; 16,20 — shock absorbers (from Jawa motorcycle); 18 — wheel (from Voskhod motorcycle); 19 — M12 bolts; 21 — M12 castellated nut; 24 — lower longitudinal bar bracket cheek (steel, sheet s2); 25 — silent block; 26 — spacer bush; 27 — distance bush.

Actually, the idea of a cargo trailer for a motorcycle is not new and has been covered quite fully in the pages of “Modelist-Konstruktor” magazine. However, the models proposed had, alongside undeniable merits, drawbacks that the author wanted to avoid in his own design. Thus, a low body position, which aids trailer stability, has its downsides. First, with the given body dimensions the trailer’s wheel track is wider than the motorcycle’s, which is undesirable because it reduces cross-country ability on loose ground (sand, ploughed land). Second, mudguards protruding above the sides hinder secure fastening of bulky loads (plywood sheets, fibreboard, etc.).

So the first design requirement was formulated: the trailer’s track must match the motorcycle’s. Further observation and analysis of industrial and home-built car and motorcycle trailers led to the rest of the requirements: maximum load capacity with minimum tare weight; signalling and lighting equipment as required by traffic rules; soft suspension with shock absorbers to damp vibrations; trailer width limited to the motorcycle-with-sidecar width; increased angle of mutual rotation between trailer and motorcycle in the coupling; reduced noise when moving; protection of cargo from wind, dust, rain, etc.; and finally, a neat appearance matching the motorcycle’s design.

The requirements for load capacity and for signalling and lighting need no explanation. Soft suspension is preferable to rigid because it better protects the cargo, especially fragile items, and reduces driver fatigue when towing.

The width limit is to ensure safety in dense urban traffic for a driver used to the motorcycle-with-sidecar dimensions.

Minimising trailer mass led to the classic form of load-bearing frame with a dropped drawbar. A high body position (at the cost of some loss of stability) had a plus: the load is farther from road dust and dirt and from oil drips from the exhaust. It should be noted that in five years of use there were no cases of the trailer overturning—neither when moving on a side slope nor in turns.

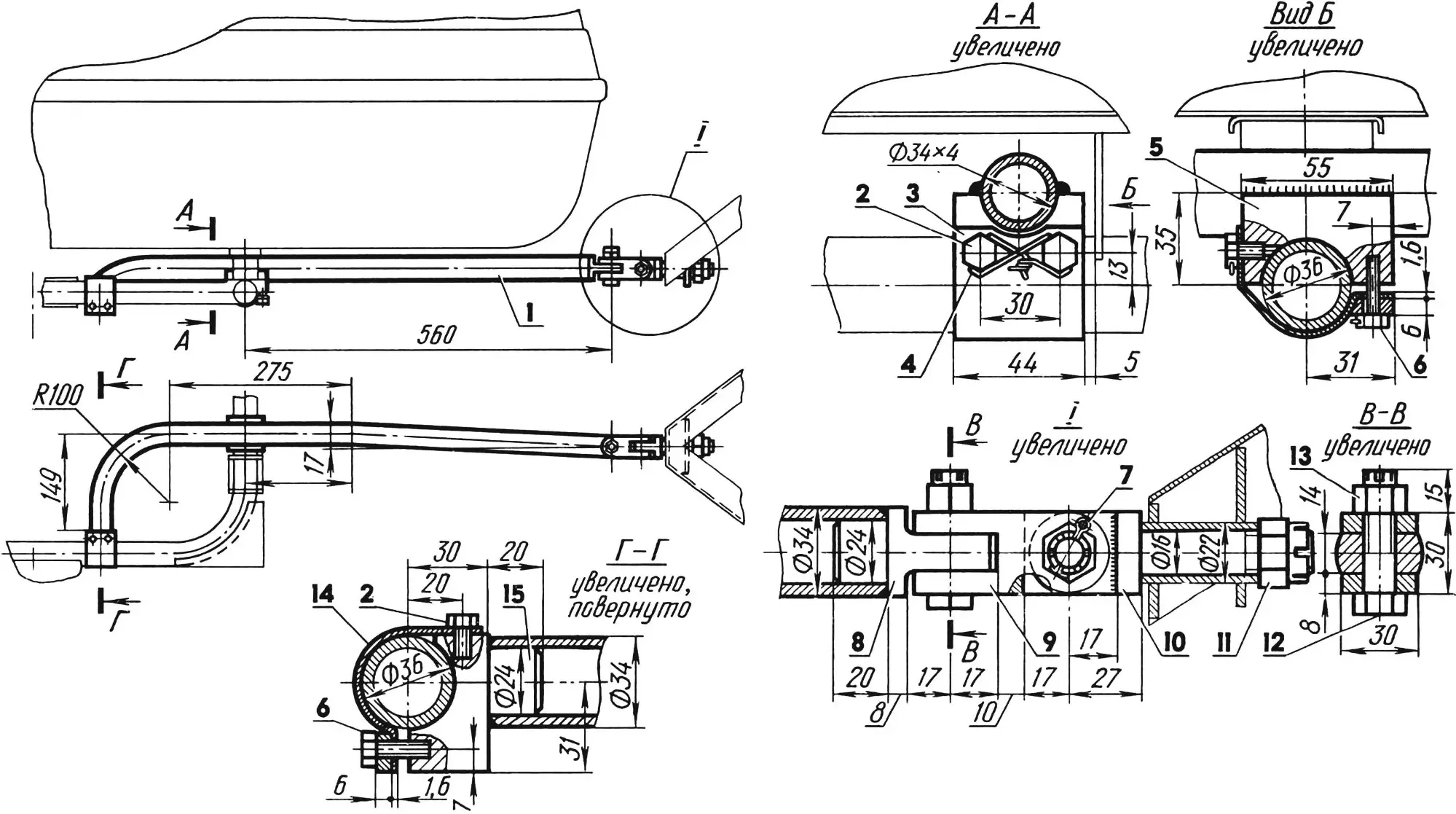

The coupling device deserves more detail. The rules require the towing vehicle and trailer to be connected by a spherical joint, in line with international standards. But the trouble is that far from all roads we travel meet those standards. It is not uncommon to see cars whose luggage racks are “decorated” with dents from their own detached trailers. One cause is exceeding the allowed angle of mutual rotation, leading to large separating forces that open the spherical joint. A motorcycle’s shorter wheelbase than a car increases the likelihood of this. So the author connected his trailer to the motorcycle with a device having three mutually perpendicular axes of rotation. This design allows the trailer to deviate left-right and up-down through an angle close to 90°, and to rotate about its longitudinal axis through practically any angle.

The coupling is under the sidecar floor and bolted to its frame. Its low position did not worsen the rig’s cross-country ability. Positioning it on the centreline of the track, however, raised doubts: would it make handling difficult? Would the motorcycle be turned by the trailer?

1 — arch (tube 34×5); 2 — M6×10 screws (4 pcs.); 3,14 — clamps (steel, sheet s1.6); 4 — lock wire; 5 — rear clamp body (steel); 6 — M6×20 screws (4 pcs.); 7 — split pin; 8,10 — eye terminals (steel); 9 — shackle (steel); 11 — M16 castellated nut; 12 — M12×45 bolt; 13 — M12 castellated nut; 15 — front clamp body (steel).

Practice dispelled those doubts. The motorcycle’s turning radius did not increase. The greater total mass did, of course, worsen the rig’s dynamics, but within acceptable limits. The motorcycle’s three braked wheels provide adequately effective braking.

The turning effect is only felt when the trailer is fully loaded and there is just one rider on the motorcycle. That situation, however, conflicts with traffic rules and with regulations that specify the ratio of maximum gross trailer mass to kerb weight of the towing vehicle (here, the motorcycle). The problem can be solved by moving some cargo from the trailer into the sidecar. If the load is indivisible, taking a passenger in the sidecar is enough.

Strength calculations gave a trailer tare weight of 90 kg and an allowable payload of 150 kg. Tests over about 10,000 km confirmed the design choices. Even with maximum but properly distributed load the rig fits well into city traffic, runs steadily on the highway at up to 90 km/h, feels confident on dirt roads and copes satisfactorily off-road.

Now about noise. The following measures help reduce it: in the coupling joints, bolts with split-pin nuts are used as pivots, allowing clearance to be taken up as it appears; the suspension linkage joints use rubber silent blocks; the standard tailgate locks were replaced with “gramophone”-type ones (as on KamAZ trucks), which hold the tailgate firmly against the side boards.

To protect the cargo from the weather there is a tent with a removable tubular frame.

The trailer is painted in the same colours as the motorcycle: body red, frame and suspension black, mudguards and wheel caps grey.

And finally, the answer to where a quarter of a tonne of cargo goes: 150 kg in the trailer, 100 kg in the sidecar and up to 20 kg on the motorcycle rack. Total 270 kg!

Modelist-Konstruktor No. 8’99, V. Shkadinov