Both at the dawn of the automobile and today, designers – whether amateur or professional – continue to try to set the car in motion using a propeller. For this purpose, both car engines themselves, motorcycle engines, and even aircraft engines are used.

Paradoxically, the well-known ancient windmills can be considered the ancestors of many modern means of transport. Indeed, remember the mill blades. Are they not, of course, in a new form, used in aviation, on most vessels – from a motor boat to a supertanker, even on some types of land transport, for example, on snowmobiles? We want to talk about another, unusual application of a bladed propeller – on cars.

Yes, among wheeled vehicles there are also vehicles that move under the action of the reactive force created by the air flow from a rotating propeller: that is why they are called aeromobiles. By design, they are close relatives of several types of transport at once – cars, airplanes and snowmobiles.

The airmobile is one of the most unusual and rare types of transport: any real designs can be counted on one hand. And this may seem strange, because at first glance they have their own significant advantages over a regular car. First of all, the airmobile is much simpler, lighter and more reliable to operate. It only has a motor with a propeller, and there is no trace of a heavy and expensive transmission. On such a machine it is possible to use a lightweight automobile-type chassis, and control is most often performed according to a similar principle: by turning the front or rear wheels. Their maximum speeds, as a rule, are much higher – up to 300 km/h, which is only possible for some sports cars.

Why are air cars so rare in the modern world? How many people are lucky enough to meet an “air car” on an ordinary highway? While their closest relatives, the snowmobiles, are flourishing and finding more and more widespread use, and have become a favorite object of creativity even among amateur designers, airmobiles have never left the experimental stage.

Everything is explained simply. There is one insurmountable drawback in such cars, which deprives them of the ability to drive on ordinary roads – the strong air flow created by the propeller. This in itself condemns this type of transport; Aeromobiles are completely contraindicated in the city, and even on dirt roads they will raise a whole cloud of dust. Another minus. A rushing air car resembles a light plane on takeoff: a terrible wind knocks you off your feet, a strong noise clogs your ears. Of course, these shortcomings are also typical for snowmobiles. But they are helped out by the fact that they are used in sparsely populated areas and do not require roads for their movement. Finally, the dangerous rotating propeller cannot be ignored.

The biography of the airmobile has not yet been completed, just as many of the problems of this type of transport have not yet been resolved.

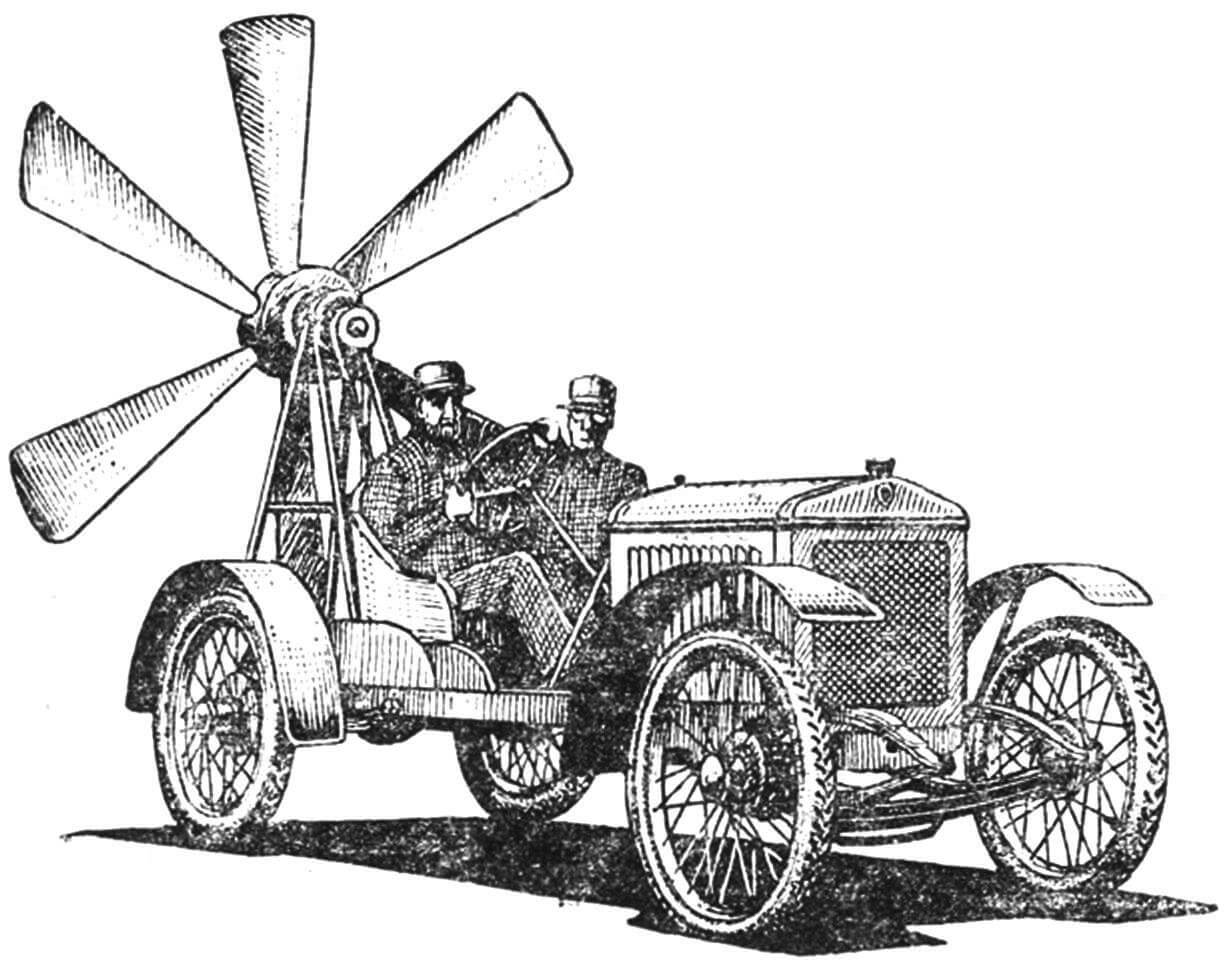

The first wheeled structures with a propeller appeared at the beginning of our century, when airplanes barely took off from the ground and “horseless carriages” allowed carriages to get around them. In those days, an airmobile was something between a car and… no, not an airplane, but rather the same windmill (Fig. 1). At the rear of the frame was a bracket for a multi-blade propeller with its own motor. Apparently, these twin-engine aeromobiles had a rational grain, which was then lost in the subsequently developed standard scheme of such machines. In any case, in the city such a crew could move on the main engine, without starting the propeller engine, but the latter was more convenient to use on a country road. However, at the same time, another important advantage of the airmobile completely disappeared – simplicity. This “windmill on wheels” cost two cars.

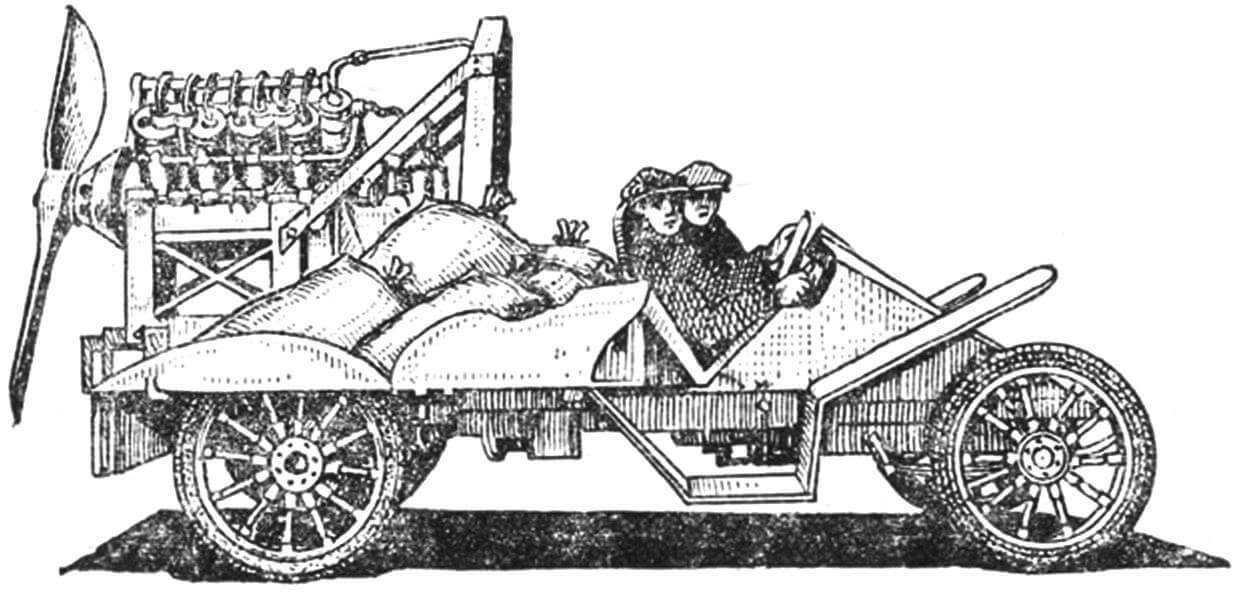

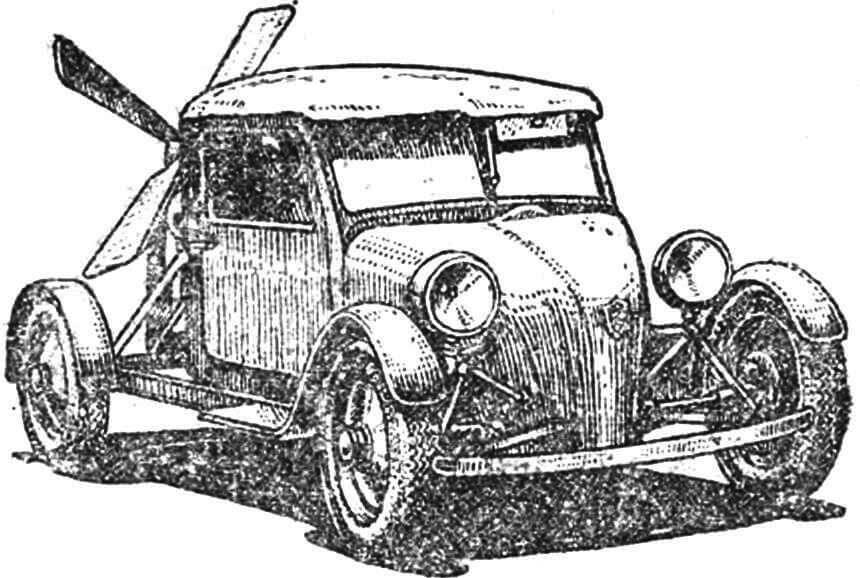

At the same time, at the beginning of the century, the layout of the air car was developed, which has existed to this day: with a motor for a rotating propeller and without a mechanical drive to the wheels. At first, the capabilities of the “wingless aircraft” were studied by aircraft designers or pilots, testing them at airfields. They served to study new aircraft engines and propellers. One of these aeromobiles (Fig. 2) was built in 1911 by the Englishman Bradshaw. On a simplified automobile chassis with a wooden frame and primitive fairings, he installed a V-shaped eight-cylinder aircraft engine with a two-blade propeller. This car with passengers exceeded the speed of 100 km/h.

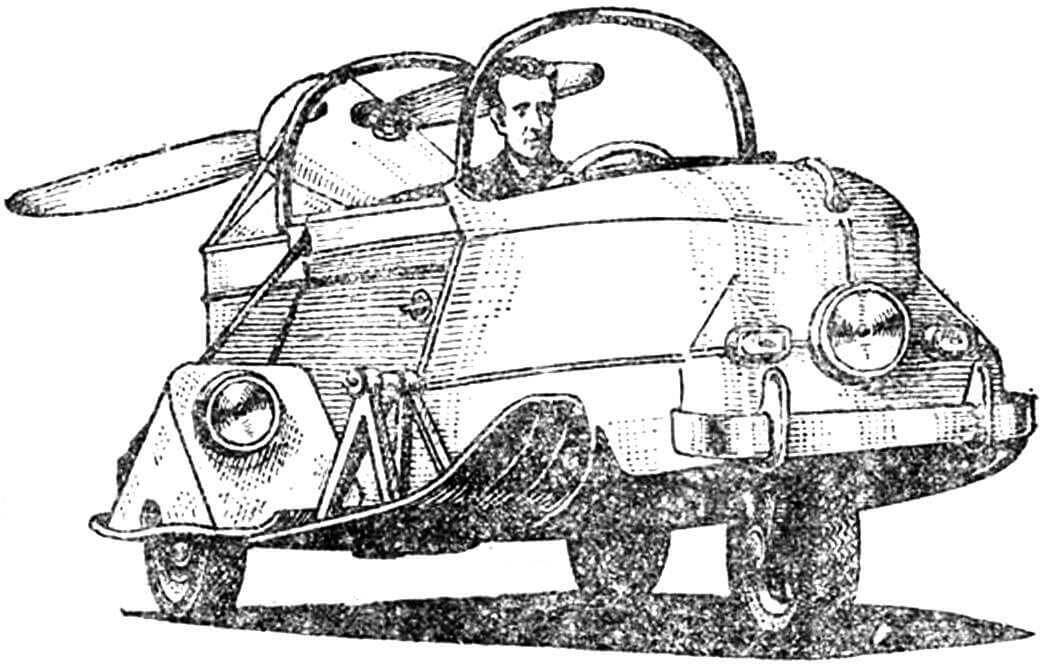

In the 20s, many inventors took up the development of air cars, which, according to the designers of that time, promised considerable prospects and benefits. Since 1913, the Frenchman Marcel Leyat had been nurturing the idea of a light “air car”, which he was able to implement only in 1920. His creation (Fig. 3) resembled a light fighter, but without wings and a stabilizer. In front, like an airplane, stood a four-bladed propeller. It was driven by a two-cylinder air-cooled engine with a volume of 1 liter and a power of only 8 liters. With. To start the engine, you had to turn the propeller by hand. Over time, the inventor made this task easier by installing a device similar to a motorcycle kick starter.

Two seats – driver and passenger – were also located like on an airplane – one after the other. The elongated body, although it seemed miniature, housed a trunk and containers for fuel and oil. The body was mounted on a lightweight chassis with independent suspension of all wheels, controlled by a cable drive, and they turned along with the axle. There were brakes only on the front wheels. The weight of the car was only 250 kg, which is approximately 2-3 times less than that of a conventional passenger car of the same class.

However, very low accelerations did not allow Leyat’s car to compete with cars, and a maximum speed of 70-80 km/h in those days was no longer anything unusual. However, it was one of the most notable early aircar designs. Moreover, it is the only one that has survived to this day: the machine is installed in one of the halls of the National Technical Museum in Paris.

In France, after the First World War, the company “Traxop Aerienne” was created, which was engaged in the development of aeromobiles. One of the most interesting appeared in 1921.

It was a two-seater car with a closed, streamlined body. The propeller was driven by a 1.5-liter aircraft engine, and all wheels had a special spring suspension. Unlike most other designs, it used pulling propellers, like on airplanes. However, practice has shown that pusher propellers for aeromobiles are more promising: the layout of all machine components is simplified and safety is increased.

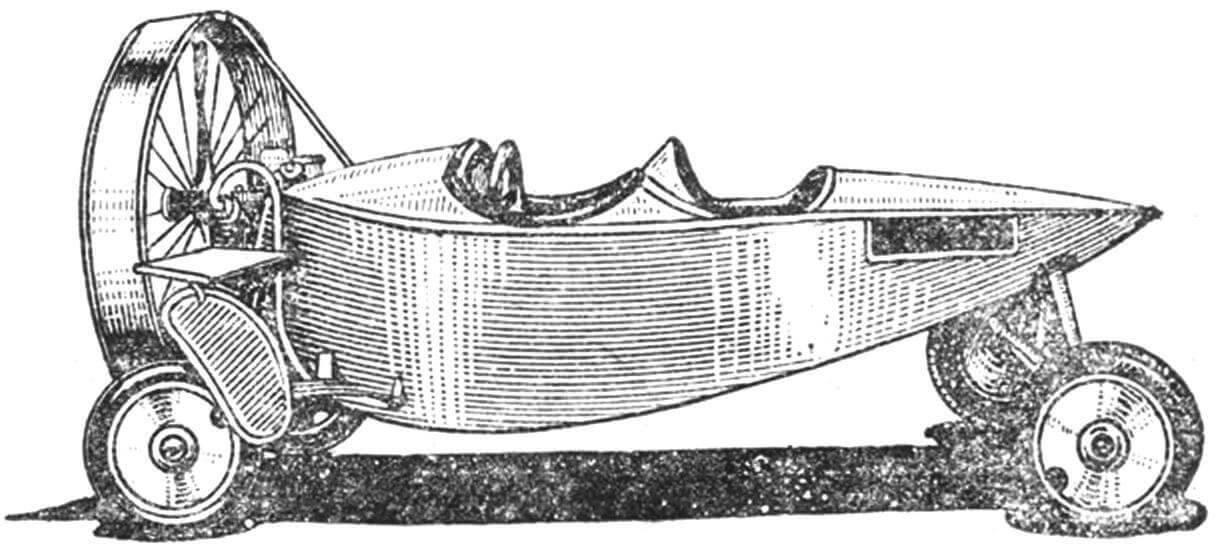

It was according to this scheme that the Hungarian Oskar Oshbot built his two-seater airmobile in 1932 (Fig. 5), the layout and appearance of which no longer showed any aviation influence. The lack of wheel drive made it possible to make the car very low, and the rounded hood, squat cabin and wheel fairings greatly reduced aerodynamic drag at high speeds. Unfortunately, history has not preserved any mention of the capabilities and fate of this machine.

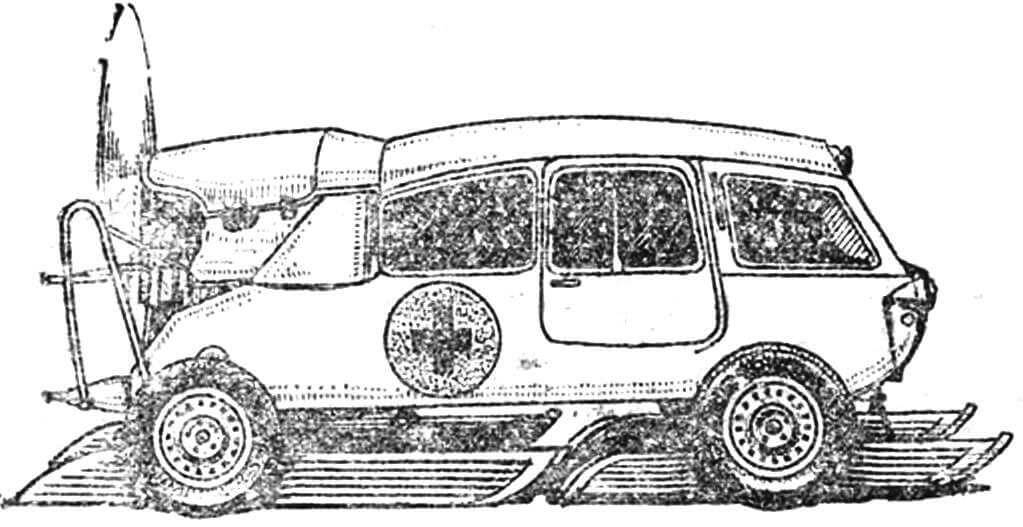

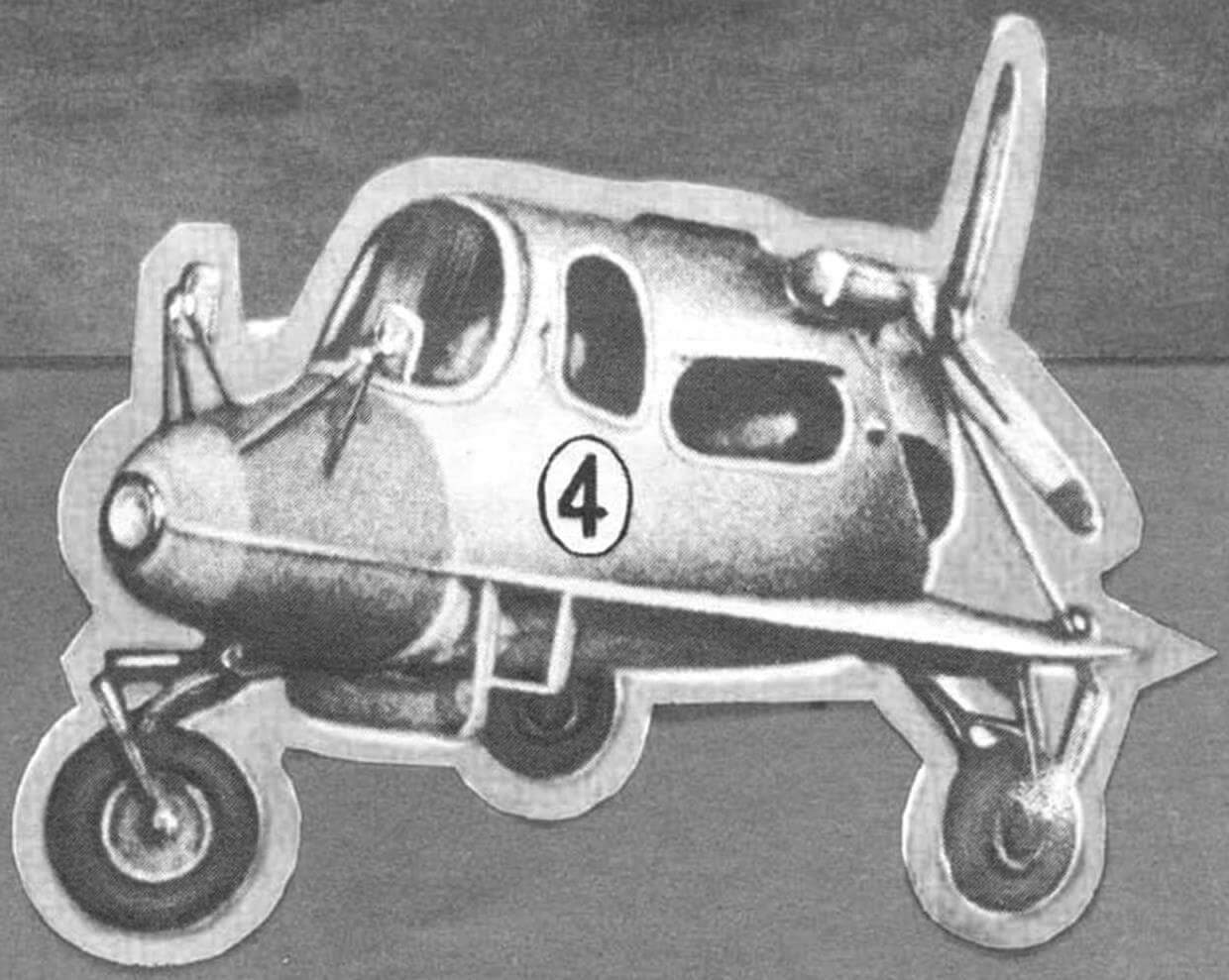

During the Second World War, attempts were made to adapt “air cars” to the needs of the army. In Germany, engineer Hans Trippel creates an all-terrain vehicle – an unusual combination of three types of transport at once: an air car, a snowmobile and a boat (Fig. 4). The streamlined body was placed on 4 hollow skis, which served for movement in the snow, and also as floats on the water. Wheels were attached to them on the outside, allowing them to ride on smooth roads without removing their skis. The unusual car was pushed forward by a propeller installed behind the body.

Despite the outward temptation of using such a universal machine in military operations, it did not justify itself: it turned out to be heavy and clumsy – the skis interfered with the wheels, the wheels interfered with the skis, and together they created enormous resistance when moving afloat. Even the aircraft engine did not have enough power, the car remained only a prototype.

Nevertheless, the idea of combining an air car with other machines turned out to be tenacious and was further developed in subsequent years.

Another airmobile design that deserves attention appeared ten years later far overseas. In 1953, the Argentine Institute of Aeronautics and Mechanics built a two-seater airmobile, called the “aerocar”. It was created on the basis of components of a standard passenger car and equipped with a streamlined two-door body, in the rear of which a Chevrolet engine with a power of 170 hp was installed. With. The body was “blown” in a wind tunnel, something that no wheeled vehicle could boast of in those years. The length was 4.6 m, width 3 m. The airmobile was distinguished by the highest performance: the maximum speed reached 264 km/h, and the acceleration time from standstill to a speed of 100 km/h was only 10 seconds. (Note that these figures have not yet been surpassed and prove the enormous capabilities of this type of transport.)

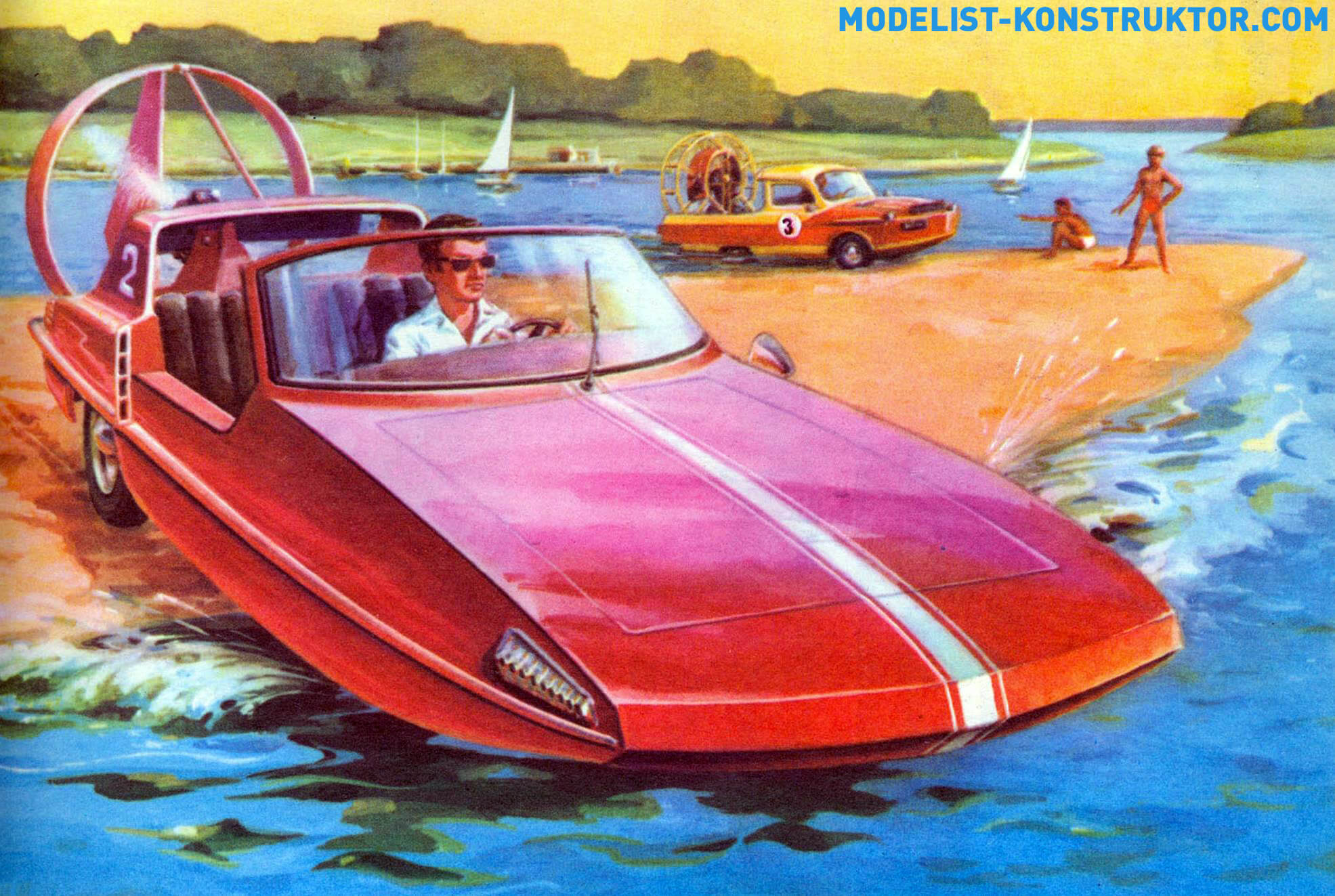

Technological progress has made adjustments to the design of air vehicles and their purpose. A new type has appeared – a universal vehicle capable of moving both on land, roads or snow, and on water.

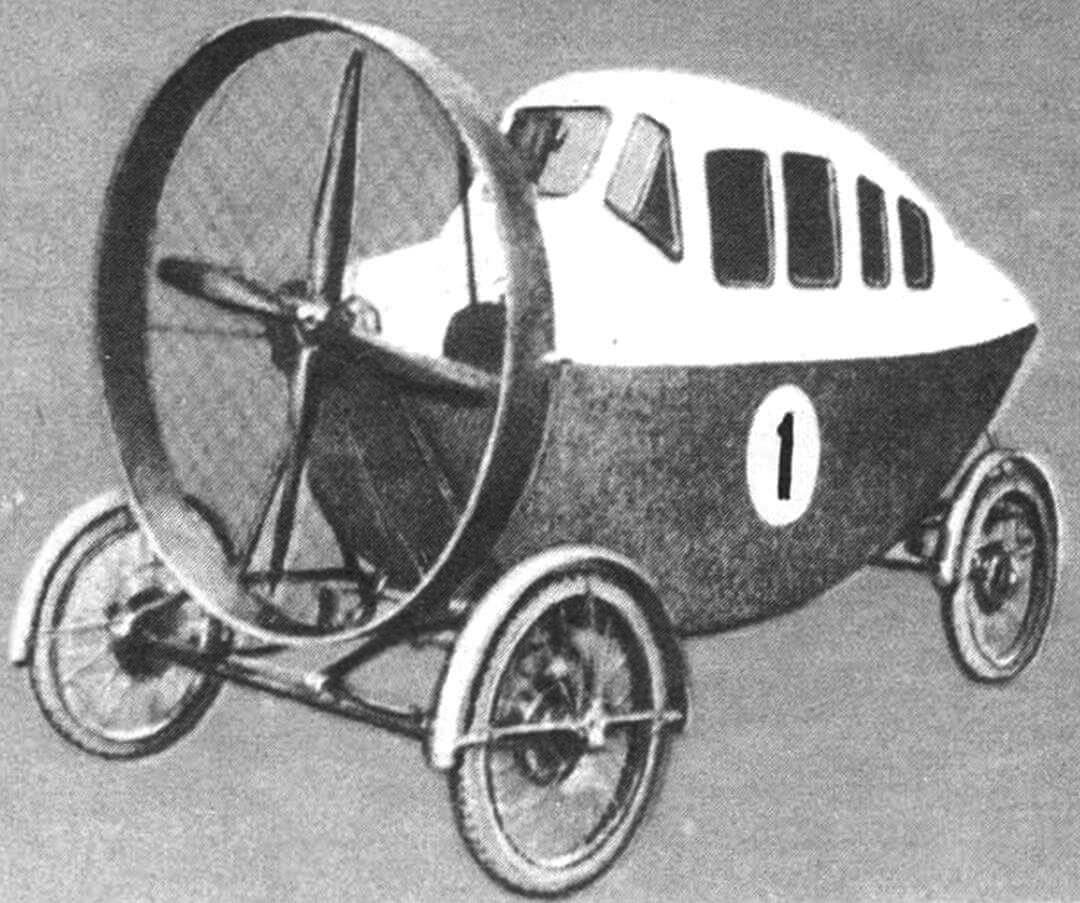

The first such car was proposed back in 1966 by an auto mechanic from Minsk Vasily Kurunkov (Fig. 6). He designed and built a single-seat three-wheeled cart using components from motorcycles and sidecars. A two-bladed propeller was installed behind the seat. It provided speeds on land of up to 120 km/h and on water 50 km/h. In addition, there were lowering skis on the sides; they could easily be replaced with a ski and a front wheel – the airmobile turned into a snowmobile. The car reached speeds of up to 80 km/h in the snow.

Two years later, a similar universal structure was built in Brazil by a group of students led by engineer R. Soleri. This is a special car with a two-seater sealed, streamlined body, very reminiscent of a boat. Steering – front dual wheels. The pushing propeller was driven by a Renault-Gordini automobile engine, but it was planned to replace it with a more powerful aircraft engine of 100 hp. With. The car reached a speed of 180 km/h on land and 25 km/h on water.

Interestingly, the propeller often dictated a body shape close to that of an airplane. Characteristic in this regard is one of the first aeromobiles of the French company Traction Aérienne (1). However, purposeful design developments are also emerging, like the experimental air car built in Brazil (2). In addition to technical aesthetics, such a design can include, for example, amphibious qualities, such as in the floating air car created by Roger Carmel on the basis of a regular Renault (3). And the Omsk mechanic V. Goloskov made his airmobile (4) all-season: in winter the wheels can be replaced with skis.

One of the interesting land aeromobiles, Aeronot, was recently built by the American inventor Alex Tremulis. His fast car is a sleek, three-wheeled, single-seater carriage with a long, cigar-shaped body and widely spaced rear wheels equipped with fairings. The machine is driven by a pusher propeller. On the chassis that served as the basis for the airmobile, the inventor also built a record-breaking motorcycle and a three-wheeled high-speed car. This “family” allows you to compare all the advantages and disadvantages of these vehicles and new types of drive.

The problem of the air car also deeply worries our amateur designers. We regularly report on their inventions. You will probably remember the interesting and unusual designs of “pure” airmobiles or combined airmobiles-snowmobiles, built by D. Antsiferov from the city of Kinel, 10. Shchegolev from Tyumen, young circle members from the Stavropol region and from Moscow (see “M-K” No. 9 , 1974). At regularly held snowmobile competitions and exhibitions, the all-season machine “Cricket” by K. Vshivtsev from the Moscow region (“M-K” No. 2, 1975) constantly attracts everyone’s attention. To many spectators and participants

During the Moscow automobile festival of 1967, I remember, perhaps, the dashing departure of L. Kapriz’s micro-aeromobile, one of the first amateur buildings in our country.

Homemade inventors bring new ideas to the design of air cars. As a matter of fact, the modern universal airmobile owes its appearance to amateur designers. It is very likely that it is their enthusiasm that will give a new impetus to the slowing development of this type of transport. And we hope that our publication will lead you to new thoughts and searches in this interesting area of technology.

E. KOCHNEV, engineer